A new decade, with new style. In the spirit of exploration, higher learning gets turned on its ear with a round of experimental concepts, telling their tales in unusual and sometimes daring visual modes, bordering on the surreal. Education also figures into the training of our fighting men in WWII, with a famous sailor reduced to classroom instruction. We even turn back the clock, to get a glimpse of education from the past – way, way past. Finally, we add to the educational picture a personage of higher authority, capable of striking fear into the hearts of most junior toons (unless he happens to have three duck nephews) – the truant officer.

Blackboard Revue (Ub Iwerks/Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 3/15/40 – Ub Iwerks, dir.) – After the abandonment of the ComiColor two strip cartoon series and his association with Pat Powers, Ub Iwerks did his best to keep his studio alive by offering his work for hire. He produced at least one advertising film, then entered into a short association with Warner Brothers, producing two Looney Tunes featuring Porky Pig. They play seamlessly enough as entries in the regular series, as Iwerks was assigned the assistance of two rising names on the Warner horizon, Chuck Jones and Bob Clampett, who, judging from the quality of the finished product and the influence that seems to appear upon Iwerks’ later productions, probably taught Iwerks a great deal about comic timing, tighter directional posing, and more reflexive physical movement (as opposed to Iwerks’ early “rubber-hose” style, or tendency to have joints and limbs animated in something of a mechanically “liquid” flow). Iwerks would next move on to Columbia studios, who seem to have thought their artists too overworked (or overpaid?) to handle the rigors of increasing color production in addition to their regular duties for Scrappy and Krazy Kat, whose shorts were becoming more labor-intensive in effort to keep up with the quality and stylistic improvements of their major competitors. Thus, Iwerks and staff were recruited to supplement the schedule with several installments each season of new Color Rhapsodies, lessening the load for the likes of Art Davis, Sid Marcus, Allan Rose and Harry Love. While some of these projects continue to bear the traditional earmarks of the Iwerks pen (two or the most notable being The Foxy Pup, which looks for all the world like a ComiColor in three strip, or Nells Yells, whose character designs bear strong resemblance to those of The Headless Horseman and Humpty Dumpty), many succeed in becoming nearly indistinguishable from Columbia’s home-grown product, or, at their best, close facsimiles of the work of Leon Schlesinger at Warner Brothers. Adding to this latter resemblance was the factor of recurrent voicing for Iwerks’ films by Mel Blanc, who was not yet under exclusive contract to Warners, and was performing a heavy amount of freelance work, both for Columbia and for Walter Lantz. All in all, the Iwerks’ Rhapsodies are a generally pleasing, if not exceptional, lot, and seem to have raised little or no complaint, budgetary or otherwise, from the tight-fisted hands of Columbia’s executives, who continued to utilize Iwerks’ services until the reassignment of production duties to Frank Tashlin, which considerably reshaped the look and structure of the studio’s future output.

Blackboard Revue (Ub Iwerks/Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 3/15/40 – Ub Iwerks, dir.) – After the abandonment of the ComiColor two strip cartoon series and his association with Pat Powers, Ub Iwerks did his best to keep his studio alive by offering his work for hire. He produced at least one advertising film, then entered into a short association with Warner Brothers, producing two Looney Tunes featuring Porky Pig. They play seamlessly enough as entries in the regular series, as Iwerks was assigned the assistance of two rising names on the Warner horizon, Chuck Jones and Bob Clampett, who, judging from the quality of the finished product and the influence that seems to appear upon Iwerks’ later productions, probably taught Iwerks a great deal about comic timing, tighter directional posing, and more reflexive physical movement (as opposed to Iwerks’ early “rubber-hose” style, or tendency to have joints and limbs animated in something of a mechanically “liquid” flow). Iwerks would next move on to Columbia studios, who seem to have thought their artists too overworked (or overpaid?) to handle the rigors of increasing color production in addition to their regular duties for Scrappy and Krazy Kat, whose shorts were becoming more labor-intensive in effort to keep up with the quality and stylistic improvements of their major competitors. Thus, Iwerks and staff were recruited to supplement the schedule with several installments each season of new Color Rhapsodies, lessening the load for the likes of Art Davis, Sid Marcus, Allan Rose and Harry Love. While some of these projects continue to bear the traditional earmarks of the Iwerks pen (two or the most notable being The Foxy Pup, which looks for all the world like a ComiColor in three strip, or Nells Yells, whose character designs bear strong resemblance to those of The Headless Horseman and Humpty Dumpty), many succeed in becoming nearly indistinguishable from Columbia’s home-grown product, or, at their best, close facsimiles of the work of Leon Schlesinger at Warner Brothers. Adding to this latter resemblance was the factor of recurrent voicing for Iwerks’ films by Mel Blanc, who was not yet under exclusive contract to Warners, and was performing a heavy amount of freelance work, both for Columbia and for Walter Lantz. All in all, the Iwerks’ Rhapsodies are a generally pleasing, if not exceptional, lot, and seem to have raised little or no complaint, budgetary or otherwise, from the tight-fisted hands of Columbia’s executives, who continued to utilize Iwerks’ services until the reassignment of production duties to Frank Tashlin, which considerably reshaped the look and structure of the studio’s future output.

Our subject film is a mix of old and new influences, combining an unusual visual style and some modern timing of dialogue with a character design which is straight out of Iwerks’ past – the final appearance of Iwerks’ trusty “old crone”, once again cast as the schoolmarm. However, even she has received a bit of updating to keep up with the times. Capitalizing on the popularity of radio’s Al Pearce and his Gang, and a somewhat screwball cooking and health commentator thereon known as “Tizzie Lish” (voiced by Frank Comstock in falsetto on the show), Iwerks’ crone adopts a facsimile of Tizzie’s voice for this cartoon. This again reinforces the resemblance of Iwerks’ product to Warner Brothers, as similar voicing had appeared at least three times in prior Warner productions, The Woods Are Full of Cuckoos, Jungle Jitters, and Porky’s Hero Agency. Our setting begins in the dead of night, as owls hoot in the trees outside, within a lonely country schoolhouse which is locked down for the evening. Inside, on the blackboard, stick-figure drawings have been made of several students in chalk. Though surviving print circulating of this film is unrestored, a rather unique exposure process may have been employed on this film to obtain the look of real chalk for the imagery, with color areas within the white outlines of the characters either coated with an extra layer of blackened wash to subdue the colors as if semi-transparent upon the black background, or photographed in double exposure to likewise give the impression of the blackboard darkening the overall color values. To the right of the students is drawn a door, uattached to any wall, and a misshaped school bell with pull rope. From out of the door appears the crone, also rendered in chalk with stick-line limbs and backbone, ready to call school into session. In the befuddled style of the “Lish” character, she apologizes to the audoence for almost missing class tonight by overdoing her “beauty sleep”. She comments that she asked her doctor how long a beauty sleep should last to be effective, to which he replied “In your case, about twenty years.” “He was kidding, don’cha think?”, she adds, “Or don’cha?” A unique touch has the crone’s chalk-line backbone sag into a serpentine curve while she wonders if the audience took the comment seriously. Teacher rings the school bell, using nearly the same up and down jumping moves on the pull rope as in Iwerks’ previous “School Days” and “Mary’s Little Lamb”. The chalk students come to life, and dash into the door under the teacher’s legs, to take their seats at outline desks drawn to the right of the uninstalled doorway. Teacher takes her place at the front of the class, and instructs the students to perform their morning exercises. She has them lift one foot, then both feet. “Now where are you?”, she asks, as the students, all suspended in mid-air, look down, and fall on their fannies. Teacher next begins a round of questions to the class. Asked to identify “the chief races of mankind”, a student answers “The Kenticky Derby and the Irish Sweepstakes.” Another student, asked what the hide of a cow is used for, responds, “to hide the cow.”

Our subject film is a mix of old and new influences, combining an unusual visual style and some modern timing of dialogue with a character design which is straight out of Iwerks’ past – the final appearance of Iwerks’ trusty “old crone”, once again cast as the schoolmarm. However, even she has received a bit of updating to keep up with the times. Capitalizing on the popularity of radio’s Al Pearce and his Gang, and a somewhat screwball cooking and health commentator thereon known as “Tizzie Lish” (voiced by Frank Comstock in falsetto on the show), Iwerks’ crone adopts a facsimile of Tizzie’s voice for this cartoon. This again reinforces the resemblance of Iwerks’ product to Warner Brothers, as similar voicing had appeared at least three times in prior Warner productions, The Woods Are Full of Cuckoos, Jungle Jitters, and Porky’s Hero Agency. Our setting begins in the dead of night, as owls hoot in the trees outside, within a lonely country schoolhouse which is locked down for the evening. Inside, on the blackboard, stick-figure drawings have been made of several students in chalk. Though surviving print circulating of this film is unrestored, a rather unique exposure process may have been employed on this film to obtain the look of real chalk for the imagery, with color areas within the white outlines of the characters either coated with an extra layer of blackened wash to subdue the colors as if semi-transparent upon the black background, or photographed in double exposure to likewise give the impression of the blackboard darkening the overall color values. To the right of the students is drawn a door, uattached to any wall, and a misshaped school bell with pull rope. From out of the door appears the crone, also rendered in chalk with stick-line limbs and backbone, ready to call school into session. In the befuddled style of the “Lish” character, she apologizes to the audoence for almost missing class tonight by overdoing her “beauty sleep”. She comments that she asked her doctor how long a beauty sleep should last to be effective, to which he replied “In your case, about twenty years.” “He was kidding, don’cha think?”, she adds, “Or don’cha?” A unique touch has the crone’s chalk-line backbone sag into a serpentine curve while she wonders if the audience took the comment seriously. Teacher rings the school bell, using nearly the same up and down jumping moves on the pull rope as in Iwerks’ previous “School Days” and “Mary’s Little Lamb”. The chalk students come to life, and dash into the door under the teacher’s legs, to take their seats at outline desks drawn to the right of the uninstalled doorway. Teacher takes her place at the front of the class, and instructs the students to perform their morning exercises. She has them lift one foot, then both feet. “Now where are you?”, she asks, as the students, all suspended in mid-air, look down, and fall on their fannies. Teacher next begins a round of questions to the class. Asked to identify “the chief races of mankind”, a student answers “The Kenticky Derby and the Irish Sweepstakes.” Another student, asked what the hide of a cow is used for, responds, “to hide the cow.”

The final shot.

Pedagogical Institution (College to You) (Fleisher/Paramount, Stone Age Cartoon, 9/13/40 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Abner Kneitel/Arnold Gillespie, anim.) – Even back in the stone age, applicants for choice positions faced the obstacle of job requirements necessitating a college degree. Fortunately, there is nearby Stonewall College, where a little professor stands before the stone-columned entrance, touting the school’s curriculum like a sideshow barker. He especially preaches the merits of the history class, “From Adam to…you’d be surprised”, tracing in the air the outline of a fenimine pnysique. Our subject youth (who we find by the end of the picture is named Joe Dokes), turned down for employment, asks to register. “To be sure “, says the professor, dragging the youth inside with the handle of his pointer cane. The student is placed in the seat of a scientific device (carved of stone, of course), with a helmet on his head to take readings from his brain. The helmet runs signals into an “Intelligence meter”, which, in a display resembling a wall thermometer, steadily descends past readings of genius, average, dimwit, half wit, and cluck, dropping to a level not even depicted by a reading on the scale, which sounds an alarm and lights up a special sign reading. “Add Oil”.

Pedagogical Institution (College to You) (Fleisher/Paramount, Stone Age Cartoon, 9/13/40 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Abner Kneitel/Arnold Gillespie, anim.) – Even back in the stone age, applicants for choice positions faced the obstacle of job requirements necessitating a college degree. Fortunately, there is nearby Stonewall College, where a little professor stands before the stone-columned entrance, touting the school’s curriculum like a sideshow barker. He especially preaches the merits of the history class, “From Adam to…you’d be surprised”, tracing in the air the outline of a fenimine pnysique. Our subject youth (who we find by the end of the picture is named Joe Dokes), turned down for employment, asks to register. “To be sure “, says the professor, dragging the youth inside with the handle of his pointer cane. The student is placed in the seat of a scientific device (carved of stone, of course), with a helmet on his head to take readings from his brain. The helmet runs signals into an “Intelligence meter”, which, in a display resembling a wall thermometer, steadily descends past readings of genius, average, dimwit, half wit, and cluck, dropping to a level not even depicted by a reading on the scale, which sounds an alarm and lights up a special sign reading. “Add Oil”.

Classes begin. Mathematics is no snap, prompting answers such as 1 + 1 = 3, 4 + 1 = 7, making the professor’s head transform into the shape of a bomb until he himself counts to 10. Geography is demonstrated with a large egg serving as the best the professor has for a globe, attempting to impress the fact that learned men are all of the opinion that the world is round. Our student hears nothing of this, as he is sound asleep. The professor procires a club from a rack marked “Brain Buster – for quicker starting”, and smashes it over the student’s dome. He asks the student again what is the shape of the earth. The student’s head is vibrating so much, it appears to divide into two heads at the same time, one answering “Round”, while the other insists, “Flat”. Following the example of the quiz/big band show, “Kay Kyser’s Kollege of Musical Knowledge”, the professor turns over the answer to the unseen audience of “STUDENTS!” The audience all calls back with the wrong answer, “FLAT!” “It’s ROUND!”, the professor insists again, and pounds upon the desk for emphasis, accidentally cracking the egg. Inside, a large dodo bird sleeps in a miniature bed within the shell, looks up, and corrects everybody, answering in what may be Jack Mercer’s first use of the gravely voice that would become Rock Bottom on Felix the Cat, “It’s square!”, then pulls the shell halves back together and goes to sleep again.

History records the name of the first man as Adam – leading to the bonehead question, “But what was Eve‘s name?” A cranial x-ray view shows the student’s brain as a sputtering auto engine, as he responds “Louise?” The professor drops a less-than-subtle hint, that he’ll get the answer “Eve-vetually”. With louder engine sputtering, our student genius finally reaches a conclusion. “Hedy Lamarr?” (A famous foreign actress of the day, notorious for nude scenes in her first film.) The professor hits the roof. He reverts to Kay Kyser form again, getting the correct answer this time from the audience, and responding with Kyser’s byline, “That’s right, you’re right”, then turns on the student with a return to the math questions. Unable again to get a correct answer from the student to “1 + 1″, he illustrates by drawing pictures of a pair of rabbits on the blackboard. “How much is one rabbit plus one rabbit?”, he demands. The student begins a series of exceedingly long complex calculations on his fingers and toes, and finally calls out the answer “777″. The professor begins chewing to bits his mortarboard, until the student points to the blackboard behind him. There, one of the two drawn rabbits gives a wink to the other, and the professor staggers backward to view the remainder of the board, now filled with chalk drawings of hundreds of rabbits. “That’s right, you’re right!”, admits the professor, his eyes crossing, replacing the tatters of his hat on his head, to fall down around his neck. An announcer indicates that after many years of this, the student finally received a diploma (shown on screen as granting the degrees of B.A., B.O., P.D.Q., R.S.V.P., T.N.T., and S.O.S., and signed by the Dean with an “X” ). Our student returns to the shop that previously turned him down, and lands the dream job – carrying a sandwich sign reading, “Get your pants pressed at Finks.”

School Boy Dreams (Columbia/Screen Gems, Phantasy (Scrappy), 9/24/40 – Harry Love, dir.) – A typical morning, with the sun rising to find the moon still in the sky, and sprouting arms to signal the moon to set and get lost. Scrappy is asleep in his bed, and hears the alarm clock ring. As he previously did in “Holiday Land”, he rises in a flash from the bed, circles the room once, then just as quickly goes back to sleep again. The clock persists in ringing, and Scrappy socks it with a right hook into the wastebasket. Mama’s call that he’ll be late to school finally gets him out of bed. A quick change of outfits is accomplished by leaving his school clothes on the bannister of the staircase, allowing Scrappy to slide down the bannister straight into them. A gulped-down meal, and Scrappy is on his way, Yippy carrying his books behind him (but making a stopoff at the first fire hydrant). Once outside, Scrappy’s energy and motivation disappear, and like the hippo in Fleischer’s An Elephant Never Forgets, he trudges along so slowly that a snail passes him. He arrives at school just short of missing roll call. The teacher, who has the cross-eyed, buck toothed face of a goon, announces there will be a substitute teacher today – Miss Lulubelle. Enter a blonde living doll (the Miss Crabtree equivalent of the animated world). All the boys in what appears to be an all male class, including little Oopie, let out with a unison wolf whistle. Scrappy darts out the door, running all the way home, just to get an apple out of a fruit bowl to present to teacher. He also pauses to throw in the wastebasket his pin-up picture of Hedy Lamarr. (What, referenced twice in the same article?). Returning to the school, he presents the choice fruit to teacher. From inside, a worm, (previously seen in the episode “A Worm’s Eye View”) appears, also gives a wolf-whistle, then reappears with his own schoolbooks and a miniature apple, seeking to enroll as a student too.

School Boy Dreams (Columbia/Screen Gems, Phantasy (Scrappy), 9/24/40 – Harry Love, dir.) – A typical morning, with the sun rising to find the moon still in the sky, and sprouting arms to signal the moon to set and get lost. Scrappy is asleep in his bed, and hears the alarm clock ring. As he previously did in “Holiday Land”, he rises in a flash from the bed, circles the room once, then just as quickly goes back to sleep again. The clock persists in ringing, and Scrappy socks it with a right hook into the wastebasket. Mama’s call that he’ll be late to school finally gets him out of bed. A quick change of outfits is accomplished by leaving his school clothes on the bannister of the staircase, allowing Scrappy to slide down the bannister straight into them. A gulped-down meal, and Scrappy is on his way, Yippy carrying his books behind him (but making a stopoff at the first fire hydrant). Once outside, Scrappy’s energy and motivation disappear, and like the hippo in Fleischer’s An Elephant Never Forgets, he trudges along so slowly that a snail passes him. He arrives at school just short of missing roll call. The teacher, who has the cross-eyed, buck toothed face of a goon, announces there will be a substitute teacher today – Miss Lulubelle. Enter a blonde living doll (the Miss Crabtree equivalent of the animated world). All the boys in what appears to be an all male class, including little Oopie, let out with a unison wolf whistle. Scrappy darts out the door, running all the way home, just to get an apple out of a fruit bowl to present to teacher. He also pauses to throw in the wastebasket his pin-up picture of Hedy Lamarr. (What, referenced twice in the same article?). Returning to the school, he presents the choice fruit to teacher. From inside, a worm, (previously seen in the episode “A Worm’s Eye View”) appears, also gives a wolf-whistle, then reappears with his own schoolbooks and a miniature apple, seeking to enroll as a student too.

After a good start, the episode falters for a middle and ending. Several incongruous shots of Yippy and the worm appear for no explainable reason but to fill time. Scrappy falls asleep over a textbook of history in the Middle Ages, going through a needless montage of shots of the teacher we’ve already seen, then dreams of rescuing the teacher as the fair damsel in the hands of the Black Knight. In a suit of armor of his own, Scrappy adjusts into high gear the stick shift of a transmission built into the saddle horn of his valiant steed, and charges the villain, chasing him over a canyon (with both knights’ horses failing to fall when the ground disappears from under them), and vanishing with the villain into a fight cloud, from which Scrappy emerges triumphant (saving the expense of drawing the battle). Scrappy awakens to find the teacher placing the dunce cap on him, amidst the other students’ laughter. End of story. The film feels like it is short a third of the reel, pressed into production without a fully-developed script. Someone come up with a better scenario for a new finish. (I thought they should at least have had the teacher walk off at the end of the day, arm in arm with Oopie, giving Scrappy the raspberry).

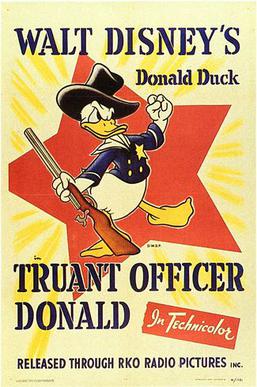

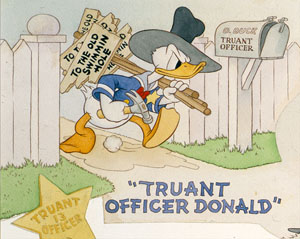

Truant Officer Donald (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 8/1/41 – Jack King, dir.) – Only Donald Duck could be heartless enough to assume the role of mean old truant officer against his own nephews. And only Huey, Louie, and Dewey could be devilish enough to play the most evil tricks on Donald to put him in his place. Our scene opens at an ol’ swimmin’ hole (probably left over from the one Oswald Rabbit frequented in 1928), where the three ducklings enjoy a dip (not skinny, mind you – they’ve brought their bathing trunks). A sign pointing the way to “School” nearby provides the perfect spying place for officer Donald, who peers at the boys through holes in the “O”;s of the sign. “Absolutely demoralizing”, fusses the stalwart upholder of the law. As one of the kids takes a dive from a springboard, Donald quickly catches him in a net before he hits water. The duckling is deposited in a flour sack, as Donald gloats, “It’s in the bag. Nephew two is caught by his swimsuit on the end of a ten foot pole, while nephew three is shot with a plumber’s helper from a harpoon gun, then reeled in. “I always get my man” is Donald’s motto. We next see Donald “escorting” the boys to school as cargo in the back of an old dog catcher’s wagon. He delivers a stern lecture to them from the driver’s cab, emphasizing that “education is absolutely essential. Crime does not pay!” However, his words are not merely falling on deaf ears, but no ears at all, as the boys have pulled out a trio of Swiss army knives, activating blades, can openers, and files, and carved away the walls of the wagon, leaving gaping holes to make their escape down the road.

Truant Officer Donald (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 8/1/41 – Jack King, dir.) – Only Donald Duck could be heartless enough to assume the role of mean old truant officer against his own nephews. And only Huey, Louie, and Dewey could be devilish enough to play the most evil tricks on Donald to put him in his place. Our scene opens at an ol’ swimmin’ hole (probably left over from the one Oswald Rabbit frequented in 1928), where the three ducklings enjoy a dip (not skinny, mind you – they’ve brought their bathing trunks). A sign pointing the way to “School” nearby provides the perfect spying place for officer Donald, who peers at the boys through holes in the “O”;s of the sign. “Absolutely demoralizing”, fusses the stalwart upholder of the law. As one of the kids takes a dive from a springboard, Donald quickly catches him in a net before he hits water. The duckling is deposited in a flour sack, as Donald gloats, “It’s in the bag. Nephew two is caught by his swimsuit on the end of a ten foot pole, while nephew three is shot with a plumber’s helper from a harpoon gun, then reeled in. “I always get my man” is Donald’s motto. We next see Donald “escorting” the boys to school as cargo in the back of an old dog catcher’s wagon. He delivers a stern lecture to them from the driver’s cab, emphasizing that “education is absolutely essential. Crime does not pay!” However, his words are not merely falling on deaf ears, but no ears at all, as the boys have pulled out a trio of Swiss army knives, activating blades, can openers, and files, and carved away the walls of the wagon, leaving gaping holes to make their escape down the road.

The boys disappear into a private clubhouse called the Pirate’s Den before Donald can catch up. Donald pounds on the door, but they reach their hands out from under it, to pull a welcome mat out from under Donald’s feet and trip him up. A peephole behind the insignia of a skull and crossbones on the door opens for a nephew to give Donald a literal horselaugh. “That’s contempt of court”, accuses Donald, and pokes his own head through the peephole to look inside. But he doesn’t see much, as he has just stuck his head into the mouth of a small cannon. The cannon is not, however, loaded with gunpowder – instead, its ammunition is a watermelon placed into a large slingshot on the other end of the barrel. Another nephew sets up a bulls-eye target at twenty paces behind Donald, while the one manning the slingshot opens fire. Donald scores a bulls eye, and the messy melon sits cracked in half on Donald’s head, resembling a football helmet. Donald next attacks with a battering ram. The kids pull the old one of opening both the front and back doors of the clubhouse just before his impact, allowing him to pass right through and collide with a greenhouse on the next lot, leaving no pane of glass unbroken, and Donald half-buried under a lily. Donald’s third attack is an attempt to jack up the entire clubhouse for transport aboard his truck. He raoses it a few feet above his head, until the kids stick a broom handle through a knothole in the floor, pressing the release button on Donald’s jack, causing the clubhouse to descend and flatten Donald into the ground.

The boys disappear into a private clubhouse called the Pirate’s Den before Donald can catch up. Donald pounds on the door, but they reach their hands out from under it, to pull a welcome mat out from under Donald’s feet and trip him up. A peephole behind the insignia of a skull and crossbones on the door opens for a nephew to give Donald a literal horselaugh. “That’s contempt of court”, accuses Donald, and pokes his own head through the peephole to look inside. But he doesn’t see much, as he has just stuck his head into the mouth of a small cannon. The cannon is not, however, loaded with gunpowder – instead, its ammunition is a watermelon placed into a large slingshot on the other end of the barrel. Another nephew sets up a bulls-eye target at twenty paces behind Donald, while the one manning the slingshot opens fire. Donald scores a bulls eye, and the messy melon sits cracked in half on Donald’s head, resembling a football helmet. Donald next attacks with a battering ram. The kids pull the old one of opening both the front and back doors of the clubhouse just before his impact, allowing him to pass right through and collide with a greenhouse on the next lot, leaving no pane of glass unbroken, and Donald half-buried under a lily. Donald’s third attack is an attempt to jack up the entire clubhouse for transport aboard his truck. He raoses it a few feet above his head, until the kids stick a broom handle through a knothole in the floor, pressing the release button on Donald’s jack, causing the clubhouse to descend and flatten Donald into the ground.

Donald gets even meaner. As the kids roast three chickens for themselves over a rotisserie fire (there’s that cannibalistic tendency again of poultry eating poultry), they smell smoke, not coming from their cooking. Donald has tunneled out from under the clubhoise, and built a fire at the mouth of the tunnel, to smoke the boys out of hiding. “Think fast, men. We’re on the spot”, says one of the nephews between coughing jags. Another of them gets the bright idea. Pointing to the nicely browned chickens, he and the others each grab the roasted birds, which just happen to be about their own size, and place their cooking under the covers of their clubhouse bed – with each chicken wearing one of the nephews’ hats. As smoke pours out the windows of the clubhose, Donald appears at the front door, thrusting it open. “Ya give up?”, Donald shouts. But there is no answer. Donald peers inside, then steps in to investigate. Spying three lumps in the bedding, Donald pulls back the sheets – and reacts in shock, at what he believes is the sight of three roasted nephews! “Why did I do it?”, he wails, bursting into tears at the bedside. The real ducklings, hwever, have escaped through a hatch in the clubhouse ceiling, and are watching this pathetic scene from above, with irrepressible snickers. They decide to really rub it in to get their vengeance on Donald, by pouring flour upon one of them, and fixing him up with a fake pair of angel wings and halo, then lowering him on a fishing line back into the clubhouse. As Donald is hit with a ray of heavenly light from above, he looks up and shudders at the sight of the descending ”angel”. Treating the vision with respect and reverence, Donald musters up his best formal greeting. “G-good morning. How art thou?” “Bend down!”, commands the spirit. As Tex Avery’s Junior would later regularly do for George, Donald cooperatively exposes his rear end, for a swift kick from the nephew. “I deserve it. I deserve it!”, admits Donald. He waits for another administering of punishment, but the nephew’s next kick is delivered with too much force, snapping the line from which he hangs. He lands atop Donald, his wings falling off, and the flour blowing away. Donald finally sees through the ruse, looks up at the broken line, and tugs on it, dragging down the other two nephews. A fight cloud ensues, and we dissolve to the aftermath – the boys, marching in unison as a sort of chain gang, tied to each other by a rope around their necks, with Donald holding the end of the rope and prodding them along ahead of him to the schoolhouse. They arrive at the school’s front door, but do not enter, as Donald receives the surprise of his life. He has not kept up on the calendar, and a notice on the door reads, “School closed for Summer holidays.” The kids, who were well aware of this all the time, shoot Donald the nastiest of glares. The embarrassed officer blushes red in the face, attempts to explain himself in double-talk, but shrinks in stature to the size of a mouse, falling out of sight off the schoolhouse steps, as the scene irises out. Nominated for an Academy Award.

Donald gets even meaner. As the kids roast three chickens for themselves over a rotisserie fire (there’s that cannibalistic tendency again of poultry eating poultry), they smell smoke, not coming from their cooking. Donald has tunneled out from under the clubhoise, and built a fire at the mouth of the tunnel, to smoke the boys out of hiding. “Think fast, men. We’re on the spot”, says one of the nephews between coughing jags. Another of them gets the bright idea. Pointing to the nicely browned chickens, he and the others each grab the roasted birds, which just happen to be about their own size, and place their cooking under the covers of their clubhouse bed – with each chicken wearing one of the nephews’ hats. As smoke pours out the windows of the clubhose, Donald appears at the front door, thrusting it open. “Ya give up?”, Donald shouts. But there is no answer. Donald peers inside, then steps in to investigate. Spying three lumps in the bedding, Donald pulls back the sheets – and reacts in shock, at what he believes is the sight of three roasted nephews! “Why did I do it?”, he wails, bursting into tears at the bedside. The real ducklings, hwever, have escaped through a hatch in the clubhouse ceiling, and are watching this pathetic scene from above, with irrepressible snickers. They decide to really rub it in to get their vengeance on Donald, by pouring flour upon one of them, and fixing him up with a fake pair of angel wings and halo, then lowering him on a fishing line back into the clubhouse. As Donald is hit with a ray of heavenly light from above, he looks up and shudders at the sight of the descending ”angel”. Treating the vision with respect and reverence, Donald musters up his best formal greeting. “G-good morning. How art thou?” “Bend down!”, commands the spirit. As Tex Avery’s Junior would later regularly do for George, Donald cooperatively exposes his rear end, for a swift kick from the nephew. “I deserve it. I deserve it!”, admits Donald. He waits for another administering of punishment, but the nephew’s next kick is delivered with too much force, snapping the line from which he hangs. He lands atop Donald, his wings falling off, and the flour blowing away. Donald finally sees through the ruse, looks up at the broken line, and tugs on it, dragging down the other two nephews. A fight cloud ensues, and we dissolve to the aftermath – the boys, marching in unison as a sort of chain gang, tied to each other by a rope around their necks, with Donald holding the end of the rope and prodding them along ahead of him to the schoolhouse. They arrive at the school’s front door, but do not enter, as Donald receives the surprise of his life. He has not kept up on the calendar, and a notice on the door reads, “School closed for Summer holidays.” The kids, who were well aware of this all the time, shoot Donald the nastiest of glares. The embarrassed officer blushes red in the face, attempts to explain himself in double-talk, but shrinks in stature to the size of a mouse, falling out of sight off the schoolhouse steps, as the scene irises out. Nominated for an Academy Award.

Blunder Below (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 2/13/42 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Tendlar/Harold Walker, anim.) – Popeye, in his newly-acquired navy white outfit aboard a battleship, attends a session of classroom instruction with the rest of the members of the crew. Seated at his desk, Popeye tries to puzzle out just what the captain, serving as instructor, is saying, which consists of complex technical jargon about the ship’s new Mark II Anti-Submarine Gun, and how to aim and fire them. To Popeye (and to most of us), it all sounds like double talk. The captain announces that the class “will have two minutes to solve that problem”, at which all the burly he-man sailors around Popeye whip out their pencils and engage in brainwork calculations, while Popeye attempts to sneak peeks at their papers, then gives a shrug to the audience as if to say, “I don’t know”. “Times up”, calls the captain, ordering everyone on deck to try out their calculations in target practice. A small destroyer tows into place a large target barge off the starboard, and each sailor is ordered into the gunnery box on the side of the ship, to mount the submarine gun and fire his round of shots at the barge. The gun operates in two modes, featuring both a wheeled base for portability on deck (an unlikely arrangement for use on a vessel in a rolling sea), and an extension mode where it can project out of the firing box on an extendable platform for greater elevation (again, only in a cartoon, not only mechanically unlikely, but it would defeat the purpose of having an armored box at all, leaving the gunner and weapon fully exposed). The first sailor tries for elevation, firing two shots which hit portions of the barge target, but are far off the bulls eye. Now comes Popeye’s turn. Popeye sneaks a look at a textbook he has stashed in his trousers for a quick refresher course, then enters the gun chamber. He emerges at twice the elevation of the last sailor, with his gun spinning around so that it is taking as many pot shots at the ship itself as at the ocean. The gun descends into the box, briefly trapping Popeye by the neck between its armored panel doors. Suddenly, Popeye emerges from the entrance door, riding the mobile gun like a wild stallion. He intercepts the captain, catching his uniform on the muzzle barrel of the gun, firing a further round of pot-shots with the captain riding out the recoils. The gun shifts into reverse gear and back into the chamber, but fires another shot at the captain, who dives into a funnel. A second shot severs the funnel just below the captain’s head, and the captain is forced to extricate himself from the steel remains like peeling off the skin of a banana. He advances on the gunnery box, but comes face to face with the gun muzzle pointing out the door. He plays a game of hide and seek, with himself at one door of the box, and Popeye and the gun rolling out the other side, meeting in the middle. More horseplay with the gun on deck, then a return to the elevating platform where Popeye rises again to an impossible height, and lets another shot fly toward the ocean. By a total fluke, he scores a direct bulls eye, and (lifting a gag from Warner Brothers’ “Porky the Gob”), a glove attached to an ultra-long telephone extender places a carnival-prize cigar into the mouth of the artillery gun. That is, until Popeye accidentally lets loose one last shot, which sinks the destroyer.

Blunder Below (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 2/13/42 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Tendlar/Harold Walker, anim.) – Popeye, in his newly-acquired navy white outfit aboard a battleship, attends a session of classroom instruction with the rest of the members of the crew. Seated at his desk, Popeye tries to puzzle out just what the captain, serving as instructor, is saying, which consists of complex technical jargon about the ship’s new Mark II Anti-Submarine Gun, and how to aim and fire them. To Popeye (and to most of us), it all sounds like double talk. The captain announces that the class “will have two minutes to solve that problem”, at which all the burly he-man sailors around Popeye whip out their pencils and engage in brainwork calculations, while Popeye attempts to sneak peeks at their papers, then gives a shrug to the audience as if to say, “I don’t know”. “Times up”, calls the captain, ordering everyone on deck to try out their calculations in target practice. A small destroyer tows into place a large target barge off the starboard, and each sailor is ordered into the gunnery box on the side of the ship, to mount the submarine gun and fire his round of shots at the barge. The gun operates in two modes, featuring both a wheeled base for portability on deck (an unlikely arrangement for use on a vessel in a rolling sea), and an extension mode where it can project out of the firing box on an extendable platform for greater elevation (again, only in a cartoon, not only mechanically unlikely, but it would defeat the purpose of having an armored box at all, leaving the gunner and weapon fully exposed). The first sailor tries for elevation, firing two shots which hit portions of the barge target, but are far off the bulls eye. Now comes Popeye’s turn. Popeye sneaks a look at a textbook he has stashed in his trousers for a quick refresher course, then enters the gun chamber. He emerges at twice the elevation of the last sailor, with his gun spinning around so that it is taking as many pot shots at the ship itself as at the ocean. The gun descends into the box, briefly trapping Popeye by the neck between its armored panel doors. Suddenly, Popeye emerges from the entrance door, riding the mobile gun like a wild stallion. He intercepts the captain, catching his uniform on the muzzle barrel of the gun, firing a further round of pot-shots with the captain riding out the recoils. The gun shifts into reverse gear and back into the chamber, but fires another shot at the captain, who dives into a funnel. A second shot severs the funnel just below the captain’s head, and the captain is forced to extricate himself from the steel remains like peeling off the skin of a banana. He advances on the gunnery box, but comes face to face with the gun muzzle pointing out the door. He plays a game of hide and seek, with himself at one door of the box, and Popeye and the gun rolling out the other side, meeting in the middle. More horseplay with the gun on deck, then a return to the elevating platform where Popeye rises again to an impossible height, and lets another shot fly toward the ocean. By a total fluke, he scores a direct bulls eye, and (lifting a gag from Warner Brothers’ “Porky the Gob”), a glove attached to an ultra-long telephone extender places a carnival-prize cigar into the mouth of the artillery gun. That is, until Popeye accidentally lets loose one last shot, which sinks the destroyer.

The captain marches Popeye into the depths of the boiler room of the ship, assigning him a coal shovel and opening the grating of the boiler door. “Fire that!”, he commands. Popeye sadly shovels coal, until an alarm bell rings, calling all hands on deck. Submarine sighted off starboard. The sailors race for the submarine guns, and let fire. But the weapon has no effect, as the periscope of the sub keeps ducking out of sight before the shells can hit. Popeye peers out various portholes at the battle, then gets hit in the face by the sub’s periscope. The periscope top protrudes inside the porthole, having a look-see. “Hey you ain’t allowed to snoop around in here”, said Popeye, socking the periscope glass so that an eye relected inside it appears to feel the pain. The periscope descends, and in an interesting underwater forward view, the sub pulls back into firing position, aims straight at the camera, and fires a torpedo which appears to be headed directly toward the lens. Popeye, dangling by his feet outside the porthole, reaches below the waterline and bends a portion of the hull of the ship into a concave curve to allow the torpedo to pass underneath without detonating. He climbs up to the main deck, where the rest of the crew continue in a barrage of shots but with no shell on target. “I regrets that there’s only one way to stop that skunkmarine”, saus Popeye, and pulls out his trusty can of spinach. Upon eating same, an x-ray view inside his arm muscle reveals the image of a firing minuteman from the then-prevalent war bonds advertisements. Diving out of his uniform with only his non-regulation polka-dot shorts on, Popeye descends into the water, with his pipe above the surface as his own private periscope. Pipe meets real periscope, as he and the vessel try to outmaneuver each other to pass. Popeye dives deeper, seeing the sub shooting out three torpedoes as if spitting the juice from chewing tobacco. A stereotype Japanese captain briefly emerges from the torpedo hole to utter a polite “So sorry.” Popeye catches all three torpedoes, and hurls them back at the sub. In neat side to side shifts, the sub dodges the explosives, then the captain again emerges with another polite “So sorry.” Not this time, as Popeye is right there to sock him one, then to add another sock to each torpedo hole to seal them shut. He grabs the tail of the vessel, and gives it a series of judo flips against the ocean bottom, then ties the bow of the craft into a knot. He carries the sub to the surface, flips it upside down, then hauls it back to the battleship, dragging it up on deck with a crane, to briefly flip around on deck like a fish just landed from a fisherman’s line. A flag pops up from inside the sub, depicting the rising sun logo of the Japanese navy, which sets rapidly, leaving the flag a blank white as a sign of surrender. The final scene has the captain and several admirals bestowing medals upon Popeye. They chant, “Your tactics are different. We’ll say that they’re different. You’re Popeye the Sailor Man.”

The captain marches Popeye into the depths of the boiler room of the ship, assigning him a coal shovel and opening the grating of the boiler door. “Fire that!”, he commands. Popeye sadly shovels coal, until an alarm bell rings, calling all hands on deck. Submarine sighted off starboard. The sailors race for the submarine guns, and let fire. But the weapon has no effect, as the periscope of the sub keeps ducking out of sight before the shells can hit. Popeye peers out various portholes at the battle, then gets hit in the face by the sub’s periscope. The periscope top protrudes inside the porthole, having a look-see. “Hey you ain’t allowed to snoop around in here”, said Popeye, socking the periscope glass so that an eye relected inside it appears to feel the pain. The periscope descends, and in an interesting underwater forward view, the sub pulls back into firing position, aims straight at the camera, and fires a torpedo which appears to be headed directly toward the lens. Popeye, dangling by his feet outside the porthole, reaches below the waterline and bends a portion of the hull of the ship into a concave curve to allow the torpedo to pass underneath without detonating. He climbs up to the main deck, where the rest of the crew continue in a barrage of shots but with no shell on target. “I regrets that there’s only one way to stop that skunkmarine”, saus Popeye, and pulls out his trusty can of spinach. Upon eating same, an x-ray view inside his arm muscle reveals the image of a firing minuteman from the then-prevalent war bonds advertisements. Diving out of his uniform with only his non-regulation polka-dot shorts on, Popeye descends into the water, with his pipe above the surface as his own private periscope. Pipe meets real periscope, as he and the vessel try to outmaneuver each other to pass. Popeye dives deeper, seeing the sub shooting out three torpedoes as if spitting the juice from chewing tobacco. A stereotype Japanese captain briefly emerges from the torpedo hole to utter a polite “So sorry.” Popeye catches all three torpedoes, and hurls them back at the sub. In neat side to side shifts, the sub dodges the explosives, then the captain again emerges with another polite “So sorry.” Not this time, as Popeye is right there to sock him one, then to add another sock to each torpedo hole to seal them shut. He grabs the tail of the vessel, and gives it a series of judo flips against the ocean bottom, then ties the bow of the craft into a knot. He carries the sub to the surface, flips it upside down, then hauls it back to the battleship, dragging it up on deck with a crane, to briefly flip around on deck like a fish just landed from a fisherman’s line. A flag pops up from inside the sub, depicting the rising sun logo of the Japanese navy, which sets rapidly, leaving the flag a blank white as a sign of surrender. The final scene has the captain and several admirals bestowing medals upon Popeye. They chant, “Your tactics are different. We’ll say that they’re different. You’re Popeye the Sailor Man.”

School Daze (Terrytoons/Fox, Nancy, 9/18/42 – Eddie Donnely, dir.) – A bit of a rough start for a series that never got past two episodes. Ernie Bushmiller’s comics character Nancy had been introduced as a bit player in the strip “Fritzi Ritz” in 1933, but rose to her own strip by 1938, together with the assistance of her pal Sluggo. The odd decision of Terrytoons to license the character (the only instance in the studio’s pre-Gene Deitch history of adapting material from an outside source) would provide a brief landmark for the industry, providing the first instance of a female child character being the central star of an animated series. Her nearest rival, Marge’s Little Lulu, seemed to be a year or two behind Nancy in development, first appearing in printed form in 1935, then making the move to animation at Paramount a year later than Nancy in late 1943. No doubt Marge’s work was influenced by the competition with Bushmiller, right down to the introduction of Tubby as a Lulu counterpart to Sluggo. Yet, despite being first to the screen, Nancy’s film career would be the briefest of brief. It’s hard to say why. Some of it may have been the uneasy marriage of disparate talents between Bushmiller’s vision and the Terry studio’s artists and directors. Marge’s choice to sign with Paramount studios was an inspired move, as Paramount had already developed a reputation for making stars out of female characters, with the past breakout career of Fleischer’s own creation, Betty Boop, and the ongoing strong personality of Olive Oyl in the Popeye series – all of which allowed said studio to provide Lulu with a series of inspired plots and well-delineated character development throughout her five-year run. Terrytoons, however, had no such track record, nor familiarity with working with female characters beyond operatic melodrama damsels in distress such as Fannie Zilch. The lack of creative vision as to where exactly the series should go seems to display itself in this first episode, which is unable to arrive at a single lineal storyline to support its brief six and one half minutes, instead settling on sandwiching three separate vignettes into one film, like a random set of short comic strips. (Paramount’s first Lulu cartoon would include a couple of minutes of short ideas to resemble Marge’s one-panel gags for the Saturday Evening Post, but would quickly shift gears into a definite plot for the last five minutes, introducing the audience to a style representative of where the series was really going.)

School Daze (Terrytoons/Fox, Nancy, 9/18/42 – Eddie Donnely, dir.) – A bit of a rough start for a series that never got past two episodes. Ernie Bushmiller’s comics character Nancy had been introduced as a bit player in the strip “Fritzi Ritz” in 1933, but rose to her own strip by 1938, together with the assistance of her pal Sluggo. The odd decision of Terrytoons to license the character (the only instance in the studio’s pre-Gene Deitch history of adapting material from an outside source) would provide a brief landmark for the industry, providing the first instance of a female child character being the central star of an animated series. Her nearest rival, Marge’s Little Lulu, seemed to be a year or two behind Nancy in development, first appearing in printed form in 1935, then making the move to animation at Paramount a year later than Nancy in late 1943. No doubt Marge’s work was influenced by the competition with Bushmiller, right down to the introduction of Tubby as a Lulu counterpart to Sluggo. Yet, despite being first to the screen, Nancy’s film career would be the briefest of brief. It’s hard to say why. Some of it may have been the uneasy marriage of disparate talents between Bushmiller’s vision and the Terry studio’s artists and directors. Marge’s choice to sign with Paramount studios was an inspired move, as Paramount had already developed a reputation for making stars out of female characters, with the past breakout career of Fleischer’s own creation, Betty Boop, and the ongoing strong personality of Olive Oyl in the Popeye series – all of which allowed said studio to provide Lulu with a series of inspired plots and well-delineated character development throughout her five-year run. Terrytoons, however, had no such track record, nor familiarity with working with female characters beyond operatic melodrama damsels in distress such as Fannie Zilch. The lack of creative vision as to where exactly the series should go seems to display itself in this first episode, which is unable to arrive at a single lineal storyline to support its brief six and one half minutes, instead settling on sandwiching three separate vignettes into one film, like a random set of short comic strips. (Paramount’s first Lulu cartoon would include a couple of minutes of short ideas to resemble Marge’s one-panel gags for the Saturday Evening Post, but would quickly shift gears into a definite plot for the last five minutes, introducing the audience to a style representative of where the series was really going.)

While Terry’s second and last Nancy outing, Doing Their Bit, was substantially more focused in its storyline, the improvement may have come too little and too late to catch the eye of the distributors or Fox executives. The other potential problem with Terry’s handling of the project was that, while it appeared that the Terry staff could handle the mechanics of movement and visual depiction of the Bushmiller characters, and even went to the trouble of hiring new personnel to provide convincing youthful voices, there is a certain lack of spark and zing to the hero and heroine’s portrayal. First, there is no character conflict, as Nancy and Sluggo are always in agreement. Second, their motives seem too squeaky-clean to be genuinely interesting, always being too interested in doing civic good There is thus no “edge” established for the characters, leaving them with little or nothing to call recognizable personality traits. Did Bushmiller think this simplicity was necessary to make the characters appear likeable on the screen? Or were the Terry boys just without inspiration as to what strengths, weaknesses, and quirks might best fit the comic creations? (Paramount, in contrast, would quickly establish Lulu with recurring adversaries, fixations with slingshots and lollipops, a talent for mischief and pranks despite initially good intentions, and an occasional selfish streak that would even lead to internal battles between her good and bad conscience in one of her earliest episodes – plus a later rocky relationship in her friendship with Tubby. Strong elements to build scripts upon, and memorable enough to allow an audience to get inside the character’s head, and have some basic expectation of what Lulu might do in a given situation – though the writers would usually come up with one better than the expectations might provide.) Whether Bushmiller was dissatisfied wuth the final product, whether Terry merely found the royalty payments not worth the returns the films were getting, or whether an executive order from the top found performance dissatisfactory enough to call for a screeching halt to production, may never be known. All that is certain is that Nancy would never reach the superstar status of Lulu on the screen – and that all probability would indicate that, had fortunes been reversed, and the respective properties been signed to the opposite studios, dame fortune might just as easily have shone upon the brunette with frizzy hairdo as opposed to the one in looping curls.

While Terry’s second and last Nancy outing, Doing Their Bit, was substantially more focused in its storyline, the improvement may have come too little and too late to catch the eye of the distributors or Fox executives. The other potential problem with Terry’s handling of the project was that, while it appeared that the Terry staff could handle the mechanics of movement and visual depiction of the Bushmiller characters, and even went to the trouble of hiring new personnel to provide convincing youthful voices, there is a certain lack of spark and zing to the hero and heroine’s portrayal. First, there is no character conflict, as Nancy and Sluggo are always in agreement. Second, their motives seem too squeaky-clean to be genuinely interesting, always being too interested in doing civic good There is thus no “edge” established for the characters, leaving them with little or nothing to call recognizable personality traits. Did Bushmiller think this simplicity was necessary to make the characters appear likeable on the screen? Or were the Terry boys just without inspiration as to what strengths, weaknesses, and quirks might best fit the comic creations? (Paramount, in contrast, would quickly establish Lulu with recurring adversaries, fixations with slingshots and lollipops, a talent for mischief and pranks despite initially good intentions, and an occasional selfish streak that would even lead to internal battles between her good and bad conscience in one of her earliest episodes – plus a later rocky relationship in her friendship with Tubby. Strong elements to build scripts upon, and memorable enough to allow an audience to get inside the character’s head, and have some basic expectation of what Lulu might do in a given situation – though the writers would usually come up with one better than the expectations might provide.) Whether Bushmiller was dissatisfied wuth the final product, whether Terry merely found the royalty payments not worth the returns the films were getting, or whether an executive order from the top found performance dissatisfactory enough to call for a screeching halt to production, may never be known. All that is certain is that Nancy would never reach the superstar status of Lulu on the screen – and that all probability would indicate that, had fortunes been reversed, and the respective properties been signed to the opposite studios, dame fortune might just as easily have shone upon the brunette with frizzy hairdo as opposed to the one in looping curls.

As for the cartoon, our scene opens upon a group of “real life” children heading for school. Their spirits are dragging, as a narrative song indicates that they view their edcational experience as a bore. A teacher not dissimilar in looks to Scrappy’s dream girl asks the class what could be done to boost their interest in learning. The students each pull out copies of a Nancy comic book, and insist that life’s lessons can all be provided by a careful study of what Nancy would do in the pages of her strip in any given situation. (Already, the premise of the cartoon has reached the stage of improbability – and likely the point where the audience’s interest tuned out.) Three short stories are presented by the kids as examples to the teacher, each sharing only the common theme of Nancy endeavoring to forward a good cause. (This would again become the central theme of the second cartoon, built arounf Nancy’s efforts to raise funds for the U.S.O. – do normal kids have nothing better to do than be civic minded?) In the first segment, Nancy carries a sign through the town, advertising Civic Pride Week, but becomes upset when she finds a box of old clothes and rags left outside a local establishment on the sidewalk. She insists the owner remove it, and the proprietor suggests that Nancy take it away herself. Carrying the box with her, Nancy examines the contents, and decides, old as they are, that the garments are too nice junk to throw away. She arrives at a compromise, by dressing up the town with them, including fire plugs, lamp posts, ice wagon horses, and every dog and cat in town. Vignette two shifts her attention to an anti-noise campaign, assisted by Sluggo. Taking a stack of handbills each, they begin to paper the town with notes reading “Quiet, please.” The segment begins to look like a remake of Popeye’s Sock a Bye Baby, as the kids attempt to silence a crying baby and a dog pursuing a cat by providing their flyers to the noisemaking culprits. But a passing motorist honking his horn is too fast to distribute the flyers to, spinning the kids around like a top and scattering the handbills everywhere. The kids decide the campaign hasn’t got enough publicity to be effective, and round up the members of their “Chipmunk Club” fo ideas on how to better spread the word. Their solution – hold a public parade, with loud horns and big bass drum to advertise the cause, making more noise than the sources they are trying to prevent. Vignette number three shows Nancy and Sluggo shifting to yet another cause – civil defense. Having no money to buy bonds, they decide to use the members of the Chipmunk Club again to form their own civil defense squad, organizing and standing a watch over what they consider the most important location in town – the local candy and ice cream parlor. The film abruptly ends without a closing wrapup in the schoolroom or a true topper gag – not even having the teacher get hooked on the comics – leaving the impression that the writers not only didn’t know how to begin or sustain a true plot, but how to end it either. It’s simply a film that, try as you might, one can’t get excited about.

As for the cartoon, our scene opens upon a group of “real life” children heading for school. Their spirits are dragging, as a narrative song indicates that they view their edcational experience as a bore. A teacher not dissimilar in looks to Scrappy’s dream girl asks the class what could be done to boost their interest in learning. The students each pull out copies of a Nancy comic book, and insist that life’s lessons can all be provided by a careful study of what Nancy would do in the pages of her strip in any given situation. (Already, the premise of the cartoon has reached the stage of improbability – and likely the point where the audience’s interest tuned out.) Three short stories are presented by the kids as examples to the teacher, each sharing only the common theme of Nancy endeavoring to forward a good cause. (This would again become the central theme of the second cartoon, built arounf Nancy’s efforts to raise funds for the U.S.O. – do normal kids have nothing better to do than be civic minded?) In the first segment, Nancy carries a sign through the town, advertising Civic Pride Week, but becomes upset when she finds a box of old clothes and rags left outside a local establishment on the sidewalk. She insists the owner remove it, and the proprietor suggests that Nancy take it away herself. Carrying the box with her, Nancy examines the contents, and decides, old as they are, that the garments are too nice junk to throw away. She arrives at a compromise, by dressing up the town with them, including fire plugs, lamp posts, ice wagon horses, and every dog and cat in town. Vignette two shifts her attention to an anti-noise campaign, assisted by Sluggo. Taking a stack of handbills each, they begin to paper the town with notes reading “Quiet, please.” The segment begins to look like a remake of Popeye’s Sock a Bye Baby, as the kids attempt to silence a crying baby and a dog pursuing a cat by providing their flyers to the noisemaking culprits. But a passing motorist honking his horn is too fast to distribute the flyers to, spinning the kids around like a top and scattering the handbills everywhere. The kids decide the campaign hasn’t got enough publicity to be effective, and round up the members of their “Chipmunk Club” fo ideas on how to better spread the word. Their solution – hold a public parade, with loud horns and big bass drum to advertise the cause, making more noise than the sources they are trying to prevent. Vignette number three shows Nancy and Sluggo shifting to yet another cause – civil defense. Having no money to buy bonds, they decide to use the members of the Chipmunk Club again to form their own civil defense squad, organizing and standing a watch over what they consider the most important location in town – the local candy and ice cream parlor. The film abruptly ends without a closing wrapup in the schoolroom or a true topper gag – not even having the teacher get hooked on the comics – leaving the impression that the writers not only didn’t know how to begin or sustain a true plot, but how to end it either. It’s simply a film that, try as you might, one can’t get excited about.

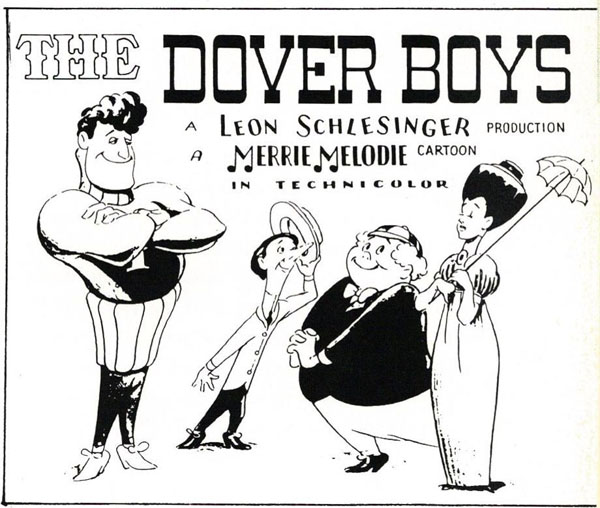

The Dover Boys at Pimento University, or the Rivals of Roquefort Hall (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 12/19/42 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.), seems to have more about schooling in its title than in the cartoon. However, as it is nominally about college life, and in view of its popularity as an experimental landmark in Warner cartoons, it deserves a very honorable mention. The film is stylistically animated in deliberately rigid and stilted fashion, seemingly to give it the stoic atmosphere of old Gay ‘90’s photographs, with its few sudden moves depicted by a method called “smear” animation – changing from one extreme pose to another in a matter of one or two frames, by way of a cel that expands the character’s image as a solid mass extending between the leftmost outlines of position 1 and the rightmost outlines of position 2. Its faux-melodramatic setting is rendered even more comically rigid by the overly-formal narration of John McLeish (Goofy’s “How To” man). Writer Ted Pierce provides anonymous voice work for the Dovers themselves, with a singing assist from The Sportsmen.

The Dover Boys at Pimento University, or the Rivals of Roquefort Hall (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 12/19/42 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.), seems to have more about schooling in its title than in the cartoon. However, as it is nominally about college life, and in view of its popularity as an experimental landmark in Warner cartoons, it deserves a very honorable mention. The film is stylistically animated in deliberately rigid and stilted fashion, seemingly to give it the stoic atmosphere of old Gay ‘90’s photographs, with its few sudden moves depicted by a method called “smear” animation – changing from one extreme pose to another in a matter of one or two frames, by way of a cel that expands the character’s image as a solid mass extending between the leftmost outlines of position 1 and the rightmost outlines of position 2. Its faux-melodramatic setting is rendered even more comically rigid by the overly-formal narration of John McLeish (Goofy’s “How To” man). Writer Ted Pierce provides anonymous voice work for the Dovers themselves, with a singing assist from The Sportsmen.

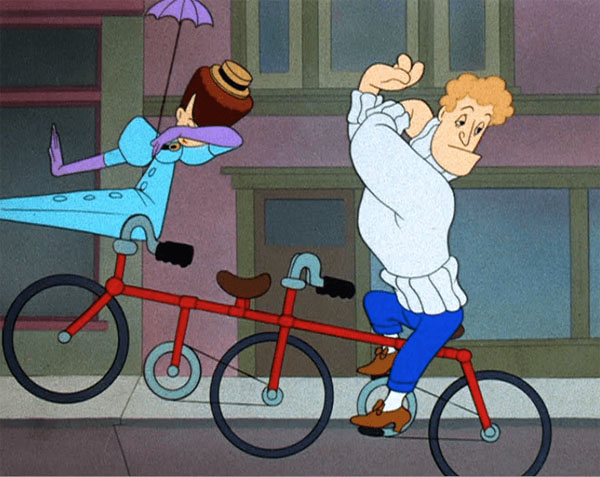

The noble campus of Pimento University (good old P.U.) provides the setting, where our three heroes Tom, Dick, and Larry, are “out and away the most popular fellows”. In fact, everyone on campus seems stalwart and true – excepting one mysterious, unshaven, stoop shouldered bum who randomly wanders through scenes with an intermittent hopping walk as a running gag throughout the picture. The Dovers seem to spend most of their time rolling along in near motionless fashion upon their own choice of wheeled conveyances – Tom, on a tandem bike which he rides solo as if performing a wheelie, Dick on an old velocipede, and Larry on a kiddie tricycle. They are off to meet “their fiancee” (an interesting arrangement, indeed), dainty Dora Standpipe, at Miss Cheddar’s Female Academy close by. Dora is as rigid as the trio, with hemline so long you never see her feet when walking, so that she appears to slide along the floor whenever moving. At the appointed hour of three, she emerges on an upper story balcony of the school like a cuckoo clock figure, to deliver a “Yoo hoo” to each of the three brothers. Accepting a motionless ride upon the handlebars of the tandem bike, doing nothing to pedal so that the bike is still ridden at a wheelie angle, Dora joins the boys on their way for a “gay outing in the park”.

The noble campus of Pimento University (good old P.U.) provides the setting, where our three heroes Tom, Dick, and Larry, are “out and away the most popular fellows”. In fact, everyone on campus seems stalwart and true – excepting one mysterious, unshaven, stoop shouldered bum who randomly wanders through scenes with an intermittent hopping walk as a running gag throughout the picture. The Dovers seem to spend most of their time rolling along in near motionless fashion upon their own choice of wheeled conveyances – Tom, on a tandem bike which he rides solo as if performing a wheelie, Dick on an old velocipede, and Larry on a kiddie tricycle. They are off to meet “their fiancee” (an interesting arrangement, indeed), dainty Dora Standpipe, at Miss Cheddar’s Female Academy close by. Dora is as rigid as the trio, with hemline so long you never see her feet when walking, so that she appears to slide along the floor whenever moving. At the appointed hour of three, she emerges on an upper story balcony of the school like a cuckoo clock figure, to deliver a “Yoo hoo” to each of the three brothers. Accepting a motionless ride upon the handlebars of the tandem bike, doing nothing to pedal so that the bike is still ridden at a wheelie angle, Dora joins the boys on their way for a “gay outing in the park”.

Their path, however, forces them to pass a certain “public house “ of ill repute – a tavern and snooker parlor, so unsightful to our heroes and heroine that they are forced to shield their eyes from its sight when passing. Inside, the former sneak of Roquefort Hall, coward, bully, cad, and thief, and arch enemy of the Dover Boys, Dan Backdlide, “squandors his misspent life” over a smoke-filled corner snooker table. Rising from the cloud of tobacco fumes, Dan utters the work “Hark”, which appears in smoky letters from his lips. Hearing the Dover Boys outside, Dan takes a full minute to overact in screaming dialogue about how much he hates the Dover Boys, but loves sweet Dora – for a whispered reason – “Father’s money.” He shouts epithets at the Dovers such as “Drat them! Double Drat them!” (Explaining where Dick Dastardly stole his catch phrase from decades later.) Dan further states that the Dovers “drive me to drink!”, and demonstrates by zipping to the bar, where a bartender repeatedly fills Dan’s shot glass in split-second motions, inbetween sneaking one drink for himself. The narrator “brings the curtain down” (literally), on this “sordid scene”, and transports us by a flip of the background to a local park, where the good guys engage in a “spirited game of hide-and-go-seek” with Dora counting while hiding her eyes behind a tree. The Dovers all have different ideas on where to hide, and each tries to convince the other that their spot is better – leading to endless changes of positioning as they zip from one end of the park to another, then back into the town, and finally reach a consensus on the one place that Dora will never find them – beneath the snooker table in the public house! (So much for their high sense of morals.) Seeing the Dovers in this unlikely locale, Dan realizes that “Dora must be alone and unprotected.” He emerges from he tavern, and spots a small “horseless carriage” of a car. With no subtlety whatsoever, Dan, in his usual screaming dialogue, states, “A runabout. I’ll steal it! No one will ever know!” (Excepting anybody within five city blocks of his vocal chords.) He proceeds to the park, to find Dora still counting. He lifts her into the car, but her grip on the tree is so strong, the whole thing is uprooted, and taken into the car with her. Suddenly realizing his error after proceeding a bit down the road, Dan drives back to the park, replaces Dora and the tree where he found them, then consults a “Handbook of Useful Information”, which includes a chapter on “How best to remove young lady from tree” – with a pair of tire irons!

Their path, however, forces them to pass a certain “public house “ of ill repute – a tavern and snooker parlor, so unsightful to our heroes and heroine that they are forced to shield their eyes from its sight when passing. Inside, the former sneak of Roquefort Hall, coward, bully, cad, and thief, and arch enemy of the Dover Boys, Dan Backdlide, “squandors his misspent life” over a smoke-filled corner snooker table. Rising from the cloud of tobacco fumes, Dan utters the work “Hark”, which appears in smoky letters from his lips. Hearing the Dover Boys outside, Dan takes a full minute to overact in screaming dialogue about how much he hates the Dover Boys, but loves sweet Dora – for a whispered reason – “Father’s money.” He shouts epithets at the Dovers such as “Drat them! Double Drat them!” (Explaining where Dick Dastardly stole his catch phrase from decades later.) Dan further states that the Dovers “drive me to drink!”, and demonstrates by zipping to the bar, where a bartender repeatedly fills Dan’s shot glass in split-second motions, inbetween sneaking one drink for himself. The narrator “brings the curtain down” (literally), on this “sordid scene”, and transports us by a flip of the background to a local park, where the good guys engage in a “spirited game of hide-and-go-seek” with Dora counting while hiding her eyes behind a tree. The Dovers all have different ideas on where to hide, and each tries to convince the other that their spot is better – leading to endless changes of positioning as they zip from one end of the park to another, then back into the town, and finally reach a consensus on the one place that Dora will never find them – beneath the snooker table in the public house! (So much for their high sense of morals.) Seeing the Dovers in this unlikely locale, Dan realizes that “Dora must be alone and unprotected.” He emerges from he tavern, and spots a small “horseless carriage” of a car. With no subtlety whatsoever, Dan, in his usual screaming dialogue, states, “A runabout. I’ll steal it! No one will ever know!” (Excepting anybody within five city blocks of his vocal chords.) He proceeds to the park, to find Dora still counting. He lifts her into the car, but her grip on the tree is so strong, the whole thing is uprooted, and taken into the car with her. Suddenly realizing his error after proceeding a bit down the road, Dan drives back to the park, replaces Dora and the tree where he found them, then consults a “Handbook of Useful Information”, which includes a chapter on “How best to remove young lady from tree” – with a pair of tire irons!

As Dora finally counts to 1500, she opens her eyes to discover her predicament. The car passes the public house, and she has the car pause long enough to make three screams for help to Tom, Dick, and Larry. (How did she know they were under the snooker table after all?) The three heroes pause in poses aghast at the sight of Dora’s plight – yet rigidly freeze there instead of moving a muscle to follow her. Dora is driven up a winding mountain road to a remote hunting lodge. Locked inside with Dan, she pounds on the door, screaming for help outside, as Dan advances. Without a second of hesitation, or an interruption in her screams, she picks up Dan bodily and tosses him across the room, destroying half the furniture in the place in the process. Help is, however, also on the way from outside, in the form of an alert young scout, who peers through the window with a long-distance telescope, even though he is close enough to see everything with the naked eye. He darts over miles of hills, pauses at a clearing, and pulls out a pair of signal flags, wig-wagging a message to another. The other scout is in fact standing right in front of him, taking the message down. He in turn darts off – two feet, into a telegraph office of “Mr. Morse”, and wires a message into town. At the snooker parlor, the Dovers receive the telegram, which consists of one word – “HELP!!”, signed Dora, “35 cents collect”. Rather than pay, the Dovers spring out of their frozen frame, and trample the messenger boy, returning to their wheeled conveyances and zipping up the steep mountain road (instinctively knowing where to go, since Dora never included the address in the telegram). Meanwhile, Dora is demonstrating that she is not one to be trifled with, as Dan is becoming more and more battered from judo flips and reverse kicks that Dora effortlessly pounds him with while maintaining her non-stop chorus of screams for help. Exhausted on the floor, and with blackened eye, Dan himself resorts to calling, “Help, Tom! Help, Dick! Help, Larry!” The boys finally arrive, but are in no mood to offer Dan assistance. Tom enters in heroic pose, itching to utter the challenging words, “Unhand her, Dan Backslide”, but can’t seem to figure where to aim them, misdirecting the challenge everyplace except to Dan’s face (including to a mounted moose head, an empty fireplace, and to his own brothers). “Hey, we’re getting in a rut”, Tom confides to the audience. The boys finally locate the prone Dan, and strike a blow upon him. The already groggy Dan offers no resistance, and remains barely standing in wobbly form after the first blow. “Oh, you haven’t been thrashed enough yet, eh?”, says Tom, and each of the boys rears back to deliver a haymaker punch. But Dan collapses between them, leaving the boys’ knockout punches aimed squarely upon each others’ jaws. All four of them lay in a heap on the floor, as Dora exits, arm in arm with the mysterious bum who’s reappeared all through the picture.