The Mexican writer Amparo Dávila (1928–2020) is known for uncanny, nightmarish short stories full of strange visitations and sudden violence. Reading The Houseguest, a sampling of her work translated into English by Audrey Harris and Matthew Gleeson, my thoughts turned toward several people I love who are suffering from alcohol dependency, depression, or other mental health afflictions worsened by the isolation and unemployment caused by COVID-19. These conditions sometimes feel to me like evil spirits, loosed by social chaos, and they are all the more disturbing because of the ways they trick their hosts into participating with them. I find myself waking up at night worrying, strategizing useless things I could do, and I’m possessed by dark thoughts. Viewed in this light, the world teems with demons of the kind Dávila writes about—there’s nothing unrealistic about them.

Born in 1928 in the Zacatecas region, Dávila moved to Mexico City in 1954 and became the secretary and protégée of the prominent writer Alfonso Reyes. Though never prolific, she eventually won almost every major award in Mexico, and in 2015 the country’s first prize for fantastical fiction was named after her. Dávila has an ingenious way of setting up an eerie premise and then withholding something crucial from the reader. In one of the stories in The Houseguest, a woman’s bedchamber becomes a prison each night, but we don’t find out what happens there; in another, a man sits in the stairwell of his apartment building and devotes himself to suffering, though we never know why. In “Moses and Gaspar,” a man inherits two pets who destroy his life—all that’s clear about the nature of the creatures is their malice. The title story features a woman terrorized by the guest her husband has invited in, whom the reader only slowly starts to realize may not be human. What exactly he is, Dávila doesn’t say. She doesn’t go in for neat endings, either: when the woman eventually traps the houseguest in his room and starves him to death, the reader is happy for her, but faintly uneasy—can we really be sure which of them was the villain?

Though the stories are occasionally funny—the suffering man especially makes me giggle, with his passive aggressive, attention-seeking choice to weep in the stairwell while his neighbors walk up and down—Dávila’s brilliance is in the absences she leaves for readers to fill with our worst thoughts and feelings. Whatever kind of creature the houseguest is, he seems to embody the stress and sense of violation that comes with living in an unhappy marriage, where even your home feels unsafe. Many married people have hosted such a guest. And when the suffering man is offered sympathy by a woman he desires, he doesn’t pause for a moment in his commitment to his own pain; he even contemplates pushing her down the stairs in order to mourn her more deliciously, which is hard not to read as a dark commentary on the self-destructive, self-indulgent nature of romantic obsession. Still, Dávila never tells the reader what to think. No demon worth his horns comes into the world neatly symbolizing something.

For all their creepiness, most of the stories take place in domestic settings, and people are always cooking and eating. On the first page in “Moses and Gaspar,” two brothers describe a Christmas dinner: “ ‘We’ll have turkey stuffed with olives and chestnuts, an Italian Spumante, and dried fruit,’ ” one says. They also reminisce about their childhood, “the apple pasteles, the evenings by the fire.” The frightening houseguest likes to sneak up on his reluctant hostess while she’s cooking in the afternoons. “He ate nothing but meat,” she says. Her servant Guadalupe brings him a tray for his two meals a day, and the wife adds: “I can assure you she flung it into his room, for the poor woman was just as terrified as I was.” Then there’s a story called “Haute Cuisine,” in which the narrator describes a family tradition of eating a certain delicacy that must be boiled alive. We’re not told what kind of creature is being consumed—perhaps none that exists in nature—but we learn that it hatches during the rainy season in a vegetable plot, has black eyes that pop out of the sockets, and screams in agony as it cooks. Delicious!

A stuffed turkey breast was my version of the Christmas turkey that was the last happy meal the brothers in “Moses and Gaspar” shared together. Photo: Erica Maclean

I was curious to note that very little of the food in Dávila’s stories sounds typically Mexican, and I contacted her translators to ask why. It turned out that they had met Dávila before she died. She entertained them at home and served agua de lima, a lemonade-like specialty she made from citrus fruit grown in her garden. Matthew Gleeson, who lives in Oaxaca and cooks a lot himself, told me that the food in Dávila’s stories is nothing like the local dishes he knows “from pre-Hispanic foodways, which are still so prevalent and so deep and rich.” According to Gleeson, Dávila deliberately went against the grain of “certain folkloric currents in Mexican literature” by choosing dishes typical of a middle and upper class, a European-influenced milieu. She also layered European-isms into her language in ways that are not visible in translation, such as using the Latinate word pavo for turkey, rather than guajolote, the term that derives from Nahuatl. Since Dávila’s character-naming conventions pull from international sources, too, I wondered if these choices were intended to create another unsettling, ambiguous space for fear to creep in.

The two translators disagreed about whether it would be possible to cook Dávila’s food. Gleeson said we couldn’t know which dishes Dávila intended even when she used a specific word, which she often didn’t. The apple pasteles, for example, could be like the turnover pastries sold by German bakers in Mexico City, or a cake with a layer of apples on the top and bottom, or even an American-style apple pie. Audrey Harris, a lecturer in Latin American and Chicana/o literature at UCLA, was more encouraging, and suggested I consult the eighties-era cookbook A Taste of Mexico, by Patricia Quintana, which has midcentury Mexican recipes in the fine-dining style Dávila was referring to.

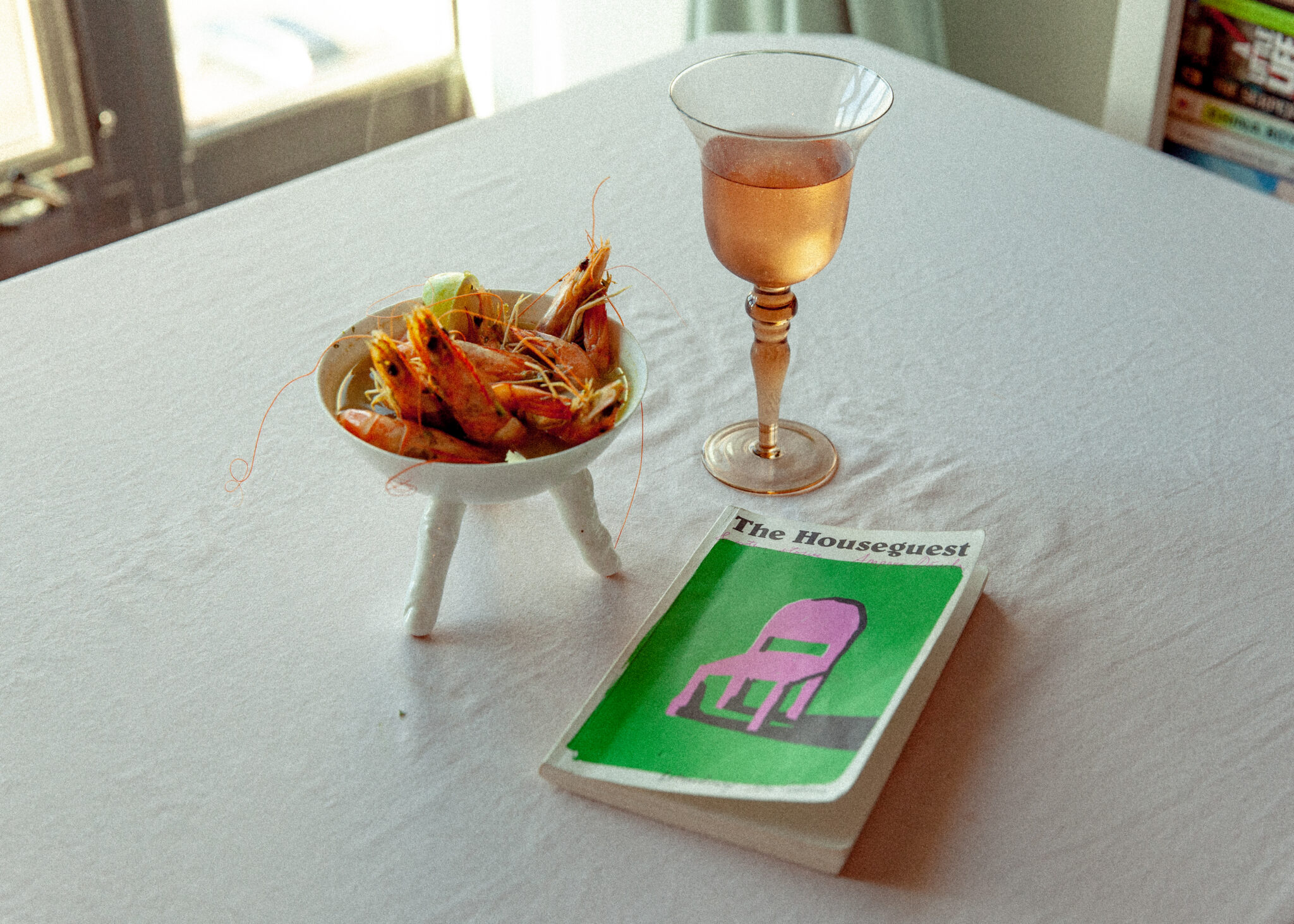

I decided to make the feast from the first page of the collection—turkey stuffed with olives and chestnuts, an Italian Spumante, and a dessert of dried fruit—and a spin on the terrifying soup from “Haute Cusine,” plus the agua de lima, the one thing we know from direct testimony that Dávila made and liked. The Christmas feast in the story would in all likelihood have involved a whole stuffed turkey; I made a stuffed-turkey-breast roulade, a more suitable portion for my nuclear family, and drew inspiration for its spicing from a stuffed pork loin in Quintana’s cookbook. For the Spumante (the word designates the fizzier type of Italian sparkling wine; Frizzante is the less fizzy type), I asked my spirits collaborator Hank Zona for a recommendation. He chose a Casina Bric Nebbiolo Brut Rosé, a relatively expensive option (at $30 a bottle) for prosecco drinkers, but still priced below fine Italian sparkling wine and Champagne. Nebbiolo is a wine-insider’s grape, which as a red wine tastes like tar and roses and has a jewellike ruby color. As a sparkling rosé, it was dry and floral, and colored a beautiful blush-beige. One of Hank’s favorite food wines, it seemed to pair well in both color and flavor with the holiday meal from “Moses and Gaspar.” To finish things off, I found what Quintana described as an “elegant recipe” that “exemplifies European influence in Mexican cuisine”—Mousse de Almendra y Ciruela Pasa, a moulded almond-and-prune mousse. This seemed appropriately fifties and Dávila-style creepy, too.

Sheets of high-quality silver gelatin and miniature molds ensured that my prune dessert would set properly and look festive. Photo: Erica Maclean

The real nightmare dish was the “Haute Cuisine” soup. Gleeson made a special plea that I cook this, suggesting that the story linked eating animals to violence, cruelty, and fear. For me, the horror of “Haute Cuisine” is not in the killing of animals but in the child narrator’s fear of the dish, and the family’s oblivious relishing of it nonetheless. The story made me think of how a family can trample on a child’s most delicate feelings in ways that might seem accidental but are usually a form of sadism made even more terrible because the child is powerless—perhaps as small and powerless as the screaming thing in Dávila’s pot. I decided to look for a creature I was afraid of eating. The ones in Dávila’s story appear in the “vegetable plot,” which could imply snails or worms. Luckily, there was a “Maguey Worms, Pachuca Style” recipe in Quintana’s cookbook. As Gleeson explained, it’s common in Mexico to eat various insects and other small creatures plucked straight from their habitat, including many kinds of grasshopper, and a large winged ant called the chicatana. I took a spin through several Mexican groceries in a Brooklyn neighborhood near mine to see if they sold worms, grasshoppers, or winged ants, but they did not. I settled for a Quintana recipe for “Green Soup,” which asked for a fish head, tail, and backbone, and sixty-four whole, head-on shrimp. Shrimp have the type of popping eyes described in the story, and I find them creepy in appearance, though good to eat.

The narrator of the story “Haute Cuisine” explains that preparing the creature was “a very complicated affair and it took time.” Photo: Erica Maclean

Lastly, agua de lima should have been simple—you grate the peel, juice the fruit, and combine with sugar and water—but it’s made from limas, a mild fruit the translators described as tasting something like bergamot but less bitter, which is not available outside Mexico. Instead I made a similar agua from limes, from a recipe in Quintana’s book.

My attempt to cook Europeanized Mexican horror-story food had its highs and lows. Quintana’s techniques seemed unnecessarily laborious, with so many seemingly illogical steps that I kept misreading them and making mistakes. I was especially flummoxed to discover that the sauce for my turkey asked for onions and garlic in both raw and roasted forms, as well as for roasted peppers. By the time I realized I’d needed to preroast, my oven was occupied with the turkey, and I could only blister the peppers last-minute over the gas flame. The flavors weren’t perfect—the soup seemed watered-down and my own improvisation in pairing a spicy sauce with the stuffed turkey was jarring—but an amazing wine can mask many sins, and the Nebbiolo was that. The surprise winner of the evening was the dish I’d expected to be bad—the prune-and-almond mousse, which tasted like a rich, fruit-topped cheesecake. I’d happily make this meal for any houseguests of mine, who are treated quite differently from the one in Dávila’s story (usually).

Agua De Limon

Adapted from The Taste of Mexico, by Patricia Quintana.

8 cups water

1 cup sugar

10 limes, zested and juiced

2 cups ice cubes

Heat water and sugar in large saucepan, until sugar is dissolved. Cool, add zest and ice, and serve.

Turkey Stuffed With Olives and Chestnuts

Adapted from Once Upon a Chef and The Taste of Mexico, by Patricia Quintana. Note: the fruit vinegar should be started five days before you plan to cook.

For the fruit vinegar:

1 quince, quartered

1 pasilla pepper, roasted

1 clove garlic, crushed

2 cups beer

4 cups water

1/2 cup brown sugar

For the turkey and stuffing:

1 tbsp olive oil, plus more for brushing

1/2 onion

2 cloves garlic

4oz mild sausage

1/4 cup white wine

1 stick cinnamon

1 curl of orange peel

1 tsp oregano

1 sprig thyme

1/2 cup chestnuts, chopped

1/2 cup olives

1 egg yolk

4 cups stuffing cubes

1 cup chicken broth

1 large turkey breast (1/2 of the whole breast), boned and butterflied

Additional olive oil, for brushing

Salt & pepper

For the sauce:

3 ancho chilies

1 onion, divided

2 cloves Garlic, divided

1/2 cup water

2 tbsp olive oil

1 tbsp brown sugar

1 tsp Mexican Oregano

1 sprig thyme

3 tbsp fruit vinegar

To make the fruit vinegar:

Combine all ingredients in a large pitcher or jar, cover with cheesecloth, and leave standing on the countertop for five days. Strain and refrigerate.

To make the turkey and sauce:

Preheat the oven to 425. Prepare a rack and roasting tray by lining the tray with tinfoil and brushing the rack with oil.

Start the sauce: Place half an onion, three ancho chilis, and one clove of garlic in a baking dish and roast until blackened and collapsed, about forty-five minutes.

While the vegetables are roasting, start the stuffing. Heat one tablespoon of oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Add the onions and cook, stirring frequently, until soft, about five minutes. Add the garlic and sausage and continue to cook, breaking up the meat with a wooden spoon, until the sausage is cooked and slightly browned, about five minutes. Add the wine, cinnamon, orange peel, oregano, and thyme, and cook for two minutes more, using your spoon to scrape up any browned bits stuck to the bottom of the pan. Remove the cinnamon stick and orange peel. Remove from the heat.

In a large mixing bowl combine the egg yolk, stuffing cubes, and chicken broth. Stir until the stuffing is moistened. Add the sausage mixture, chestnuts and olives, and stir to combine. Check seasoning and add salt and pepper to taste.

Place the butterflied turkey breast skin side down on a countertop or work surface and cover with plastic wrap. Pound the turkey breast to an even half-inch thickness. Brush the meat with olive oil, and sprinkle with salt and pepper. Spoon the stuffing in an even layer onto the breast. Starting with the long side (and choosing the part of the breast with the least skin, if possible) roll into a long sausage. It’s okay if a little stuffing is falling out. Tie with kitchen string every one and a half inches.

Remove the roasted vegetables from the oven and turn the heat down to 375. Put the ancho chilis in a gallon freezer bag and seal. When the oven is the correct temperature, place the roulade on the roasting tray and bake until a meat thermometer inserted into the thickest part of the roll registers 155, about an hour.

While the meat is cooking, make the sauce. Remove the chilis from the freezer bag and run under cold water to loosen the skin. Peel, destem, seed, and devein. Combine the chilis, the roasted garlic, the roasted onion, half a raw onion, one clove raw garlic, and half a cup of water in the blender and puree. Heat two tablespoons of olive oil in a saucepan, add the puree, the brown sugar, the fruit vinegar, and a sprig of thyme, and bring to a boil. Turn down to a simmer and cook for twenty minutes, until thickened.

To assemble, spread the sauce on a plate and top with slices of the turkey.

Green Soup

For the broth:

6 cups water

1 fish head

1 fish tail

1 cup dry white wine

1 medium carrot, peeled

1/4 white onion

1 clove garlic, whole

2 sprigs parsley

1 bay leaf

3 black peppercorns

2 tsp powdered chicken bouillon

For the soup:

2 poblano chilies, seeded, deveined, and chopped

1/2 cup parsley, chopped

1/2 cup cilantro, chopped

2tbsp white onion, chopped

2 cloves garlic, whole

2 tbsp olive oil

2 tbsp butter

Salt and pepper to taste

12 large head-on shrimp

To make the broth:

Place the water in a large saucepan or dutch oven, and add the fish head and tail, and all other ingredients for the broth. Bring to a boil, then turn down to a simmer and cook, partially covered, for one hour.

Strain, reserving the broth, carrot, and onion and discarding the other solids. Puree the carrot and onion, using a little of the broth as necessary.

To make the soup:

Combine the poblano chilies, parsley, cilantro, onion, and garlic in a food processor and puree until smooth, adding broth from the soup as necessary. Heat a skillet to medium-high. Add the olive oil, butter, and the poblano puree, and cook until thickened.

Combine the remaining broth, the vegetable puree, and the poblano puree in a large saucepan. Simmer for ten minutes. Add the shrimp and simmer for ten additional minutes, until cooked through. Salt and pepper to taste.

Serve garnished with lime wedges.

Almond-and-prune mousse

1 lb prunes, chopped

1 3/4 cup red wine

2 strips orange peel

6 tbsp plum jam

1 cup water

3 tbsp powdered gelatin, divided

2 1/2 cups raw almonds, soaked, skinned and ground

6 egg yolks, lightly beaten

2 cups plus 1 tbsp sugar

2 1/2 cups milk

1 vanilla bean

1/2 tsp almond extract

1 cup heavy cream

1 cup sour cream

Heat prunes with wine, orange peel, and jam in a small saucepan. Cook until the mixture thickens to the consistency of a thick jam, about twenty-five minutes. Remove peel. In another pan, moisten one tablespoon powdered gelatin in half a cup of water and heat until dissolved. Stir in prune mixture, mixing well. Let cool.

Line a nine-inch gelatin mold with saran wrap. Pour prune mixture into mold and refrigerate for forty minutes.

Meanwhile, puree almonds, egg yolk, sugar, and milk in a blender or food processor. Pour into a saucepan. Add vanilla bean and almond extract. Cook over low heat, stirring constantly, until mixture comes to a boil. Remove from heat, remove vanilla bean, and cool slightly.

Moisten two tablespoons powdered gelatin in half a cup of water, and heat until dissolved. Add to the almond mixture and stir.

Combine heavy cream and sour cream and whip until peaks form. Carefully fold into almond mixture. Pour the almond mixture into mold over prune mixture. Chill for four hours or overnight.