Whole-hog barbecue is a specialty of the rural South. Ricky Parker, who passed away in 2013, was the owner of B. E. Scott’s Barbecue in Lexington, TN. In 2004, he agreed to let David apprentice for a week–the hardest week of the year: July Fourth. Here’s a recounting of David’s literal trial-by-fire education. (Scott’s is still open, and we encourage you to visit!)

Traveling west between Nashville and Memphis, across the rhinestone buckle of the Bible Belt, I headed deeper into the South’s other and equally worshipped belt—that of barbecue. Every few miles, advertisements for pulled-pork sandwiches shared billboard space with promises of salvation from ministers who looked as if they should be presiding over a congregation of used-car salesmen, not sinners. Stapled to telephone poles were handmade signs with the letters “BBQ” and a hastily drawn arrow underneath.

Few things other than barbecue could wrench me from the familiar comfort of my air-conditioned New York apartment and drop me into western Tennessee, especially in the torpid heat of late June. It wasn’t because of any abiding love for the food, but rather because of a colossal, unmitigated lack of understanding. Having been raised in New England during the culinarily unenlightened ’60s, I took anything my father put on our hibachi to be barbecue. Steak? Yep. Hot dogs? Certainly. And while you’re at it, why not grilled cheese made with Velveeta? But later, as the cult of pork crept north, I found myself at swank eateries downing Kansas-, Texas-, and Memphis-style barbecue, and I was none the wiser. It seems no two people who have ever huddled over a pit have agreed upon what animal to cook, how to cook it, whether to sauce it, or when to season it. There isn’t a technique that confounds me more, and, considering how barbecue is suddenly the food of the moment, I figured I needed to learn more.

I contacted my friend southern food writer John T. Edge, a short, wiry man whose face has the scrubbed shine of a just-opened lichee nut, and asked him where I could go to learn about barbecue firsthand.

“B. E. Scott’s, in Lexington,” he didn’t hesitate over the phone. “To me, one of the top two or three places in the country. It’s owned by Ricky Parker.” And that was how I found myself in a rented Toyota Camry whose speedometer I kept shimmying at the 50 mile-per-hour mark. For the moment, I was content to let the stereotype of the gruff Southern state trooper with a neck the size of a sewer pipe remain just that. Because of an irrational fear of authority and polyester uniforms, encountering one of the South’s finest in the flesh didn’t factor into my plans. Neither did pit stops. To combat a rather delicate condition that often arises when traveling—unaccountably the moment I discover the next rest area is 60 miles away—I swigged from a bottle of Imodium. All in all, it should be a pretty good trip, I told myself.

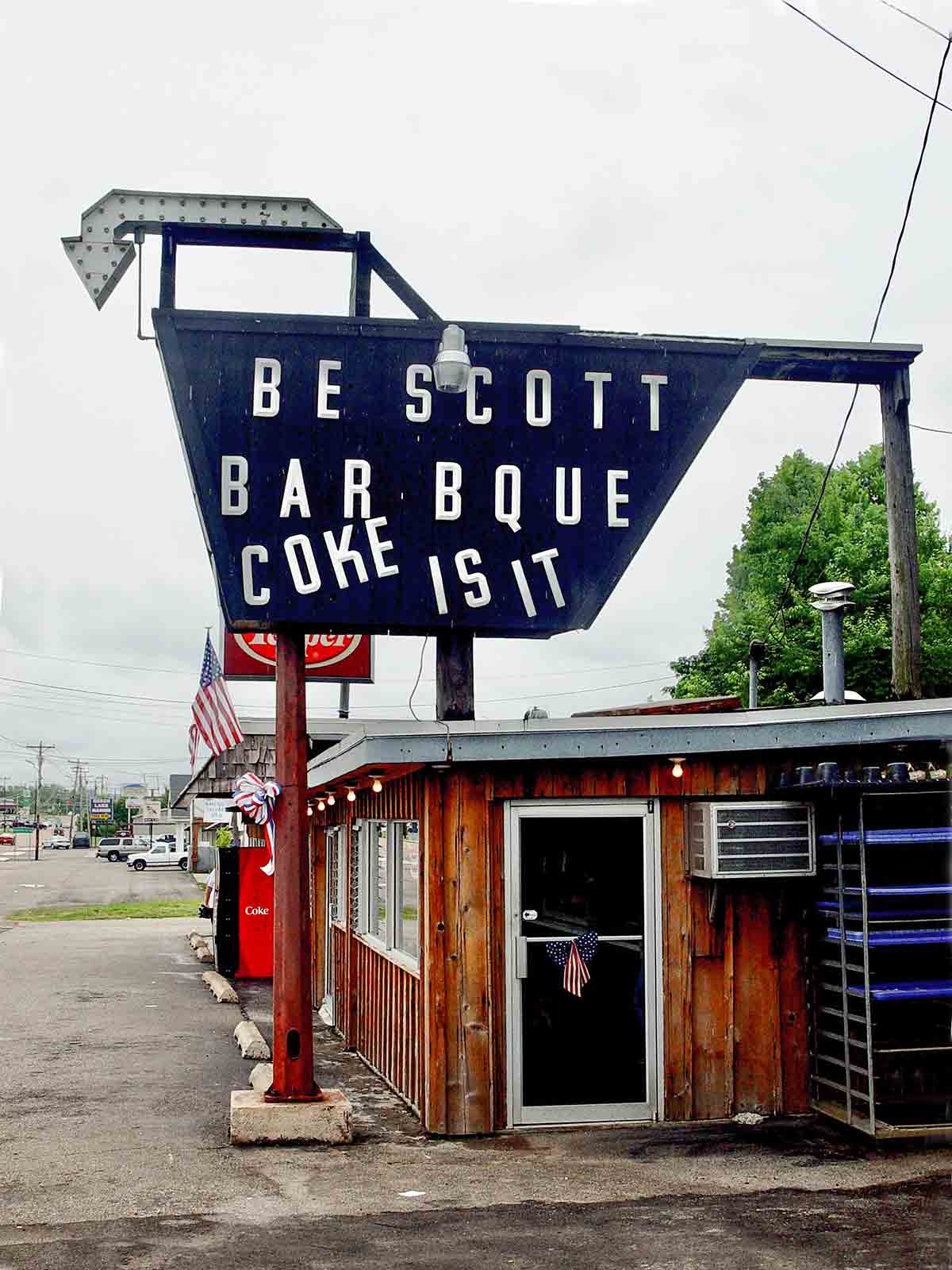

Two hours later I pulled into the Econo Lodge, diagonally across Highway 412 from Scott’s. I squinted against the sun and saw the empty parking lot. I remembered Ricky told me his place was closed on Mondays. The building was squat with wood-slat siding and a flat roof. To the right was a garage, and the area between contained two concrete-block pits and a wood-kindling shed, all of which were enclosed by a chain-link fence. I hesitate to call it a restaurant, although there’s a sizeable dining room off to one side that was rarely used during my visit; the bulk of Ricky’s business is takeout, so the hub is the order window. Joint doesn’t fit because of the connotations of shifty-eyed men with bad teeth and women who can tie a knot in the stem of a Maraschino cherry with only their tongues. Shack will have to do.

During our initial phone conversation, Ricky told me Early Scott opened the shack in 1960—one of the only places to do whole-hog barbecuing. “Then one afternoon in 1971, I showed up from the other side of town with no place to stay,” he said. “My daddy threw me out because he and me was fighting so bad.” Scott took him in and over the years taught him everything he knew. Ricky took over the business in 1989 and operates it exactly as Scott did: The sauce recipe and barbecuing techniques have remained the same, and he continues to fire only whole hogs unless a special catering request comes in from hunt clubs when he’ll barbecue all types of game from pheasant to venison. “Damn if the holidays don’t bring in a bunch of turkeys, too.”

Once inside the motel room, I collapsed on the bed, grateful for the air-conditioning. Lying there I wondered what I had gotten myself into. I’d never met this man, yet he relented, allowing me to be part of his team on two conditions: One, I go down the week ending July Fourth, his busiest time of year. And, two, I pitch in and lend a hand. I immediately agreed, but now that I was there, my gut was screaming for a Xanex.

I’m not normally a nervous traveler. I’ve ping-ponged all over Europe without giving it a second thought. But Tennessee? What the hell was I doing there? And rural Tennessee at that. I suddenly wanted to go home, where cashiers are rude, coffee costs $4.50 a cup, and Deliverance is only a movie. Knowing I couldn’t put it off any longer, I headed across the street to meet my teacher for the week, Mr. Ricky Parker.

I knocked on the side door, arousing the indignation of a heavily chained German Shepard, and waited. Nothing. I pounded again, and Ricky blustered out of the office, with four men in tow. He was lanky with long limbs that seemed to telescope at the joints like a carpenter’s ruler. A potbelly insisted itself beneath his shirt, giving him the appearance of one of those hungry-looking statues in the Egyptian wing at Metropolitan Museum of Art. The decal over his breast pocket read:

Scott’s Barbecue

Whole Hog Barbecue Cooking

His hair matted to his pink scalp and furled up at the stringy ends. A full Vandyke beard framed his mouth. His jeans were burnished dark with dirt, blood, and what I could only imagine to be pork fat. In his hand was a grease-stained baseball cap. He was a human smudge.

“Yeah?” Irritation idled in his throat. I introduced myself and his demeanor changed, suddenly gracious. He wiped his right hand on his jeans and extended it. I noticed it was calloused and pocked with burn marks. His shake was firm but welcoming.

A man with overalls and a T-shirt that smelled of sour milk leaned in, grabbed my arm above the elbow, and squeezed hard. “Hope you’re in good shape, cuz Ricky here’s gonna work your butt off.” The others laughed and closed ranks. Immediately I was back in seventh-grade gym class. Able Alves and his flunkies, smelling my fear after discovering I couldn’t climb ropes, were trying to stuff me into a locker, which, thanks to my mother’s cooking, was an impossibility.

“Ah, just ribbing ya.” He thrust his hand out: “I’m Lynn.” I looked at his arms; they were substantial. In fact, everyone’s arms were substantial. Lynn Pollock, a retired technician from Proctor & Gamble, is a friend of Ricky’s and every year volunteers his help for the July Fourth weekend. He was to become, I found out later, my supervisor. Pleading exhaustion, I declined an offer to head outside and start my education but accepted Ricky’s offer to have dinner with him and his family that night.

Back at the motel, I couldn’t shake my uneasiness about the whole venture. If I’m to be completely honest, part of my fear was the impending physicality of it all. I’m constitutionally allergic to manual labor. My last strenuous job was when I worked on a farm. My father thought of sunshine, backbreaking work, and being the brunt of farmhands’ jokes as the antidote for a morose, acne-pocked teenager. Looking back, I would have preferred medication. Overwhelmed, I laid on the bed and drifted off.

A horn honked outside. I gathered myself up, splashed water on my face, and opened the door to the blast of humid air. In the Parker minivan, I found a completely different Ricky. He was dressed in crisp brown trousers, a smart white shirt, and a dressy version of his cap—all of which made him look ten years younger. Behind me was his family: wife Tina, son Matthew, and stepdaughter Cheyanne. His other son, Zach, was away fishing.

“What do you think of Lexington so far?” Tina asked as we pulled out of the parking lot.

“Broiling. How do you people stand it?”

The van broke out in laughter. “This ain’t nothing,” said Ricky. I saw myself hauling hogs the size of refrigerators in this heat and had to question my sanity.

As Ricky barreled down the highway, regarding the speed limit as only a polite suggestion, I wondered what could possess a man to do the equivalent of an aerobics class over smoldering coals in punishing humidity, when from the year and condition of his vehicle and the roll of cash he later pulled from his pocket, he certainly could hire a team to do it.

“For the love it,” he said, “the challenge. Hell, I’m more married to my work than I am to my wife, and you can ask her right now if you don’t believe me.” Tina rolled her eyes, not a gesture of contempt or even resignation, but one of love and still-fresh admiration. Tina, by the way, is his second wife of two years. His first didn’t like competing with a pit of pigs.

“Tina and me, we’re a kind of team, right, hon?” He caught her eye in the rearview mirror, and she smiled. I imagined he was going to mention how they’ve created a system to deal with his acts of career infidelity. “See, she works at the cardiac catheterization unit at the hospital. So I clog up people’s arteries, and she cleans them out and sends them back. It’s a family business, you might say.”

She waved him off and leaned through the opening between the bucket seats. “We had a bunch of T-shirts made up. It’s got The Washington Post logo and says that we’re ranked in the top three barbecue places in the country.”

“Really? Who said that?”

The van burst out in laughter again. “You did,” Ricky said.

“I don’t work at the Post. I just wrote one article for them years ago, and it had nothing to do with barbecue.” Then I remembered John T. telling me he thought Scott’s was one of the best in the country. Did Ricky misinterpret things when I told him that over the phone? But far more important: If the Post gets wind of this, could I be sued?

“It’s in all the papers, too,” said Cheyanne.

“Oh, terrific,” I said and slumped in my seat.

At O’Charley’s, Tillie, our waitress, dragged three tables together, and we sat down. “Nice, ain’t it?” asked Tina. I looked around. Above hung a fake Tiffany lamp. Across the way, baseball flickered soundlessly from a TV.

“Now I want you to make sure everything’s just right,” Ricky said to Tillie. Then he pointed at me, “‘cuz this here’s the restaurant critic from The Washington Post.” Before I could correct him, Tillie began fluttering about, dealing big plastic menus as if they were playing cards. It was a good thing I wasn’t a critic from the Post because we had to wait nearly an hour for our food—if it could be called that—to arrive. Growing steadily impatient, Ricky downed several beers and kept doffing his hat to run his fingers through his hair.

“See, here’s the problem,” he said leaning on his elbows. “I’ve got me a whole bunch of hogs laying there in the pits, and they ain’t gonna fire themselves. If I’m gone too long, my whole schedule is messed up. I won’t have enough barbecue for the next few days.”

I didn’t buy his story of the need for round-the-clock care. “So what happens in the middle of the night?” I said trying to trip him up. “You’re not out there tending hogs. You have to sleep, don’t you?”

“No,” said Tina, absentmindedly balling up the paper from her straw between her fingers.

“Hell, I’m there sometimes two, three times a night.”

“Come on, Ricky,” I said, cocking my head to one side, sure he was overstating the truth.

What little humor he had left drained out of him like a tapped keg. He looked at me as if I had questioned his faith, or his allegiance to the flag, or the paternity of his sons. “You’ll see, Mr. David, you’ll see.”

Whether fueled by agitation, at me or Tillie, or by one too many beers, Ricky clambered into the minivan and gunned out of the parking lot, the tires screaming like a playground full of schoolgirls. On the highway, I watched the speedometer ratchet to the right. I stopped looking at 75 miles per hour. I turned back to Tina. Maybe she’d read the terror in my face and tell Ricky to slow down, but she was staring out the side window, apparently used to the Mach 1 travel.

“I’m gonna tell you somethin’,” he said to me slowly. Here it comes, I thought, my comeuppance for doubting him. “If you ever find yourself in a bind ’cause you’ve been speedin’, just tell the officer you’re a friend of ol’ Ricky Parker, here. Understand?” I nodded. “That’ll take care of everything.”

The next morning, the first day of my apprenticeship, I arrived at Scott’s a few minutes before nine to poke around. Besides the dining room, with its plastic red-and-white checkered tablecloths and the indoor takeout window crowded with cartons of soda in anticipation of the holiday, the building also housed a small, ransacked office. Perched on a shelf was a television tuned to the Weather Channel, which Ricky was glued to like a slack-jawed kid watching Saturday-morning cartoons. The weather report, he later said, told him how much hotter he had to blast the outdoor pits to compensate for nighttime cold and moisture in order to keep on schedule and to prevent the hogs from “souring”—remaining too damp for too long causing the meat to go bad. Beyond the office was a side room, where a steam table coddled canned baked beans and a refrigerator held fresh homemade coleslaw. Behind it all, sat the indoor pits.

Until then, I never gave a moment’s thought to what a real barbecue pit looked like. For all I knew, it could have been a gigantic hole in the earth in which haunted-looking kids, like those in faded photographs taken before child-labor laws were instituted, were spreading smoldering embers solely for my eating pleasure. But instead, two cinder-block structures, about fifteen feet long by six feet across by three feet high hunched in the room. Covering them were splayed-opened cardboard boxes that once contained refrigerators. They were bleeding grease and were lightly dusted in soot. The wooden posts that held up the place and the low beams overhead were covered in a sticky amber-like resin, decades of pig fat that rose from the pits daily. They were flocked with wooly fuzz, like lint from a dryer screen. On the far end of the room, two fans the size of airplane propellers exhaled smoke. I was about to look under the cardboard covers when Ricky and Lynn darted by, bottles of red liquid in their hands.

“Late!” Ricky said.

Lynn brought his face within inches of mine, cocked his head, and slowly enunciated his words, pulling on the vowels as if they were taffy. “When Ricky says naaahn, he doesn’t really mean naaahn. It’s more like eight forty-five.” I felt like a mentally challenged cocker spaniel.

“David!” I trotted through the pit and into the garage, where Ricky was standing in front of the walk-in cooler. There was a sudden tenderness in his voice. “I wanna show you something.”

Until that moment when he lugged on the door handle, the largest piece of pork I’d ever seen was a shoulder from Stop & Shop lying on its sanitary napkin in a plastic tray. But inside, hanging from a track above, were more than a dozen whole pigs, flayed open.

“Are you a religious man?” I asked.

“Not particularly. Why?”

“Well, then—holy freaking Mother of God.”

“Nice, huh?” Ricky asked, nudging his chin toward the hogs.

Their pinkness jolted me. I’d only seen that color in babies and cotton candy. I tried to turn away, but the chorus line of hogs looked so feminine. The deep indentation of the spine and the curve of the haunches looked like the sensuous shape of a woman’s back.

I’ve been privy to the slaughter of hogs before, I’d just never gotten so oppressively intimate with the results. When I was a kid in Swansea, Massachusetts, we lived next door to Mr. Miranda, the last of the gentleman Portuguese farmers. On his property, he kept several horses, a coop full of chickens, a few cows, and, his pride: a pigsty filled with hogs. Several times a year, usually late on a Saturday night, frightened squeals rose from the backwoods. “He’s murdering babies again,” my mother would mutter. I knew that he had sliced a hog’s throat, and I counted the seconds until the protests subsided. Usually, it was over in less than a minute, but sometimes if his stroke was off or the hog was particularly fierce, the pleading and choking went on and on, and my parents and I would sit there in the breezeway looking at each other. On the TV Mary Tyler Moore rolled her eyes.

We returned to the main building, and Ricky said, “There’s someone who wants to meet you.” Standing quietly in the shadows was the hulking form of Jack D. Elliott, the editor-in-chief (as well as publisher, reporter, and photographer) of the Henderson County News. He was there to interview me about why I chose Scott’s as one of the top three barbecue places in the nation.

While I parried his questions, trying to explain I had nothing to do with this top-three rumor, that I never even heard of Scott’s until a few months ago, I watched Ricky mix his trademark sauce. As I pulled out my reporter’s pad, Ricky’s shoulders stiffened, and the room fell silent. “Would you mind steppin’ out for a minute?” he said, pointing to the bottles in front of him, “I need to do this in private.”

I looked at Jack. We lowered our pads. “But Ricky, we agreed: I come down here and help, and you show me everything.”

Lynn grabbed my arm. “Don’t you worry, Ricky,” he said. “We’ll be right outside—call us when you need us.” He led Jack and me out back to the fire shed, where hickory sticks were burning.

“What the hell was that about?” I asked, pointing to the door I was just hustled through.

“Ricky—”

“Look,” I said. “I’m not dumb enough to think the man was going to hand over a recipe that has kept him in business all these years. But still, I traveled all this way to learn; he didn’t have to kick me out. I looked like an ass in there.”

“Are you done?”

I toed the ground with my sneaker. “For now.”

“Southerners are like catfish. Stick your hand in the water and get all grabby, and we’ll scatter. But put a little bait on your hook, sit back, and wait, and you’ll catch yourself a big ‘un. You just have to be patient.” Jack nodded his head. “Ricky’s the big ‘un.”

“Well, frankly, it’s dumb to chase off two writers when there’s a lot of publicity to be had.” I looked to Jack for collegial support, but he just shrugged.

Lynn chuckled. “Well, that’s him. Dumb like a fox.”

Ricky called me back inside and, as a consolation, let me finish making the sauce. Lined up along the workbench were a dozen or so plastic gallon jugs. My job was to add three cups of sugar and one cup of salt to each and shake it up. Apparently, this was Ricky’s way of assuring the recipe wouldn’t go home with me. But I could already smell the vinegar, cayenne, cumin, and see the black pepper. But I wasn’t going to tell him that. At least not yet.

Twenty minutes later, Ricky and Lynn, accompanied by Brad, Ricky’s brother-in-law, came to see if I had finished the job. Pleased with my work, Ricky led me to the front of the store. It was already lunchtime.

“But wait,” I said, pointing to the indoor pits covered with the cardboard, “how does all this work?”

“All in good time, Mr. David,” Ricky said. “All in good time.” The men smiled at each other. Why did everything seem so adolescent here? It felt like rush week at Barbecue Fraternity, and it was clear that pledging wasn’t going to be easy. At Rochester Institute of Technology and Carnegie-Mellon University, where I went to college, some pledges had to drink their body weight in beer, others had to pick an olive off a block of ice with their butts, while still others had to bear the humiliation of standing outside in a dress singing “I Feel Pretty” from West Side Story. I was beginning to fear none of that would compare to my task for the week: Getting this infuriatingly likable, wily guy to talk straight about what he does. At least getting some barbecue for lunch wouldn’t require a secret handshake.

: Agustin Oliva

: Agustin Oliva

Ricky ushered me behind the takeout window, which was chockablock with chips, racks of hamburger rolls, and a coffin-sized soda cooler. In three orderly rows against the window was a militia of fried pies: peach, apple, and, what would become my favorite, chocolate. Nothing more than giant turnovers, they were made by Ricky’s grandmother, who’s actually his great aunt, but by dint of age and affection, he refers to her as Granny.

“David, meet Mr. Carver.” A dignified black man with a slight stutter, Mr. Carver has worked at Scott’s for more than 20 years. He’s in charge of filling orders, and regardless of how long the line, he remains unruffled. Years of perfecting his workflow taught him how to arrange his counter as carefully as a sushi master, so no space or movement is wasted. In front of him was a thick plastic cutting board and his cleaver, which he used for customers who preferred chop to pulled pork. Lined up on his left was a forest of squeeze bottles, three filled with Ricky’s thin, orange-red barbecue sauce—mild, medium, and extra hot—which spiked the air with their bite of vinegar; one filled with ketchup; and the last with mayonnaise. He explained that barbecue sauce is only meant to be put on pork right before serving, otherwise, it’ll smother the hickory-smoke flavor. Beef was different, he pointed out. It can hold a lot of sauce, partly because of mesquite smoking. Within his reach were a few bags of large and regular hamburger rolls, white cardboard containers that looked like old-fashion nurses’ hats, a box of pop-up wrapping paper, and a pack of toothpicks topped with frilly green plumes.

“Hold on a minute.” He reached through a hole in the back wall that divided the takeout area from the pit and hauled a metal grate covered with foil and topped with a hog that had been smoked and slow-cooked for hours. I began to understand how things worked. Those cardboard-covered pits behind the wall were the end of an assembly line that began in the cooler, where freshly slaughtered hogs were hung. Once the hogs were cooked under one cardboard-covered pit, they were switched over to a second, most likely a holding pit. Mr. Carver then pulled up each hog through the opening to the storefront, where it’s ripped apart, muscle-by-muscle for adoring customers.

“So what’ll be?” asked Mr. Carver.

I blinked. “Um, barbecue.”

Brenda Powers, a pint-size woman who has a wicked sense of humor and an even more wicked temper, exchanged looks with Linda Britt, Ricky’s aunt, a self-described “southern belle from hell.” Both work the counter during lunch.

“Sweetheart,” Brenda said, gently squeezing my arm, “there’s a whole bunch of possibilities. Now, let’s start with something easy: Do you want a sandwich or an order of meat?”

“A sandwich, I guess.” With that, Mr. Carver fished out a roll from one of the bags and plopped it open.

“Light or dark meat?” asked Linda. Dark meat? Wasn’t pork called The Other White Meat?

“Light,” I said, confident that Madison Avenue knew something I didn’t.

“Give him catfish, Mr. Carver,” Brenda said as if I weren’t there. He plucked out a long strand of glistening meat. She saw my confusion. “That’s what we down here call the tenderloin, sweetie.”

“Now, honey, how partial are you to spicy things?” This was Linda.

“Not very.”

“Well, then, I suggest just a splash of the mild sauce, because it’s really like most people’s hot sauce.” With that, Mr. Carver upended one of the squeeze bottles and let a small drizzle fall onto the meat.

“Ketchup?”

“On pork?” Then I realized I may have made a social gaff and recanted. “Unless that’s how you folks do it down here.”

“It’s an individual thing, hon,” said Brenda unoffended. “Slaw?”

“Coleslaw,” Mr. Carver clarified. “Vinegar slaw or mayo slaw.”

“Neither.”

“Mayonnaise?”

“No.”

“Onion?” I shook my head. Mr. Carver wrapped my sandwich and handed it to me.

“Go on, now,” instructed Brenda, “and set yourself down a bit.”

I took the sandwich and headed for the door. I tried to turn the handle, but like all handles in Scott’s, it was slicked with grease. Brenda used a side towel to open it, and I sat at one of the tables in the empty dining room.

I took a bite of the sandwich and rolled the pork around my mouth. I waited for the familiar tomato-and-brown-sugar sweetness of the barbecue I had back home. What I got was a bracing bite of vinegar. On its heels was the slow build and burn of cayenne pepper and a slight insistence of cumin. Beneath it all, like a foundation, was the pork, slightly smoked and very moist and tender. Just to be sure that fact wasn’t lost on me, earlier in the day Lynn led me by the arm to the holding pit and positioned his finger on the end of a rib of a cooked hog. “How’s this for tender?” he asked. He flicked his finger and up popped the rib, not a shred of meat clinging to it. “Now, go on, mark that in your little diary,” he said, motioning to my reporter’s pad.

“Well?” asked Ricky, who loped into the dining room.

I wasn’t unimpressed, just at a loss for words. Memories of barbecue I’d had at different places back home flipped through my head, but I had no point of reference. If someone put a gun to my head (and with all the hunting talk I overheard that day it was a distinct possibility) and forced me to make a comparison, I’d have to say maybe, just maybe, chicken. But wouldn’t that be an insult? I took another bite and gave a thumbs up to avoid saying anything, Satisfaction spread across his face, and he continued out back to the wood-kindling shed.

Clearly, I was missing something, and as usual, felt guilty. The lunch customers at the takeout window were patiently lining up, waiting for their daily helpings of Scott’s barbecue. What were these people seeing that I wasn’t? I pulled at the meat with a plastic fork. It was so tender the tines barely bent. I tasted it again. I didn’t find the sandwich offensive, I wasn’t even mildly opposed to it. If anything, it was quite good. In fact, very good. The problem was expectations. In my world, barbecue was sweet, sticky, smoky, and tomato-y. Considering the unfettered recommendation of John T., I expected Ricky’s barbecue to be exponentially better—BBQ², hell, BBQ³. I expected that first bite to be some sort of homecoming. I expected the sandwich to awaken a long-dormant inner Southerner. I believed, however irrational, I’d have a sudden affection for hunting, fishing, and all-you-can-eat buffets.

Maybe Ricky’s barbecue is like fried clams, I thought. Growing up in New England, I was weaned on them—the real kind with their plump, profane bellies still attached. The craving for them seemed imprinted on some chromosome that blinkered on and off like a bulb on a string of Christmas lights. And when the light shone, I ate them by the pint full in shacks, lobster pounds, and fine restaurants up and down the Eastern seaboard. I’ve also had nearly every ill-conceived variation, including those of interlopers, chefs from other parts of the country who think they can top sweet Ipswich clams dunked in a simple batter and fried to a golden crunch. Maybe I had it all wrong about barbecue, then. Maybe K.C. Masterpiece has about as much in common with Ricky’s barbecue as Howard Johnson’s clam strips have with the fried clams from The Bite on Martha’s Vineyard. All I knew is I had only eight meals left to solve this riddle.

Early Wednesday morning, the humidity hung like moss in the air, and the walk-in cooler’s refrigerated atmosphere hit me like a welcomed cold front. “Here’s where your proper schooling starts,” said Lynn, his breath forming little smoke signals. “Dudn’t it, Ricky?” This time the hogs appeared less feminine, more like meat. If you squinted your eyes and used your imagination, they could even look like a rack of pink overcoats for the larger-size woman.

Ricky surveyed the room, marked a blue “X” on three of the hogs, and left without so much as a word. Lynn and I were charged with loading them into the pick-up truck and driving around back to the outdoor pits, which Ricky uses every July Fourth to meet the extra demand for barbecue.

The process of getting the pigs out of the cooler was like a Rubik’s cube. We had to push some off to one side, switching tracks above, the great wheels squealing in protest, in order to get to the chosen ones. Finally, when we isolated the first marked hog, Lynn heaved it my way. It hit me in the chest like a linebacker, knocking the wind out of me and smearing blood on my jeans.

We sprayed water on the rubber mat that lined the truck bed to reduce friction so the hogs could slide on and off. (My guess as to their weight: 190 to 200 pounds, although Ricky never revealed the exact number, and Mr. Carver leaned heavily on his stutter to avoid the issue.) When we released the hogs from the hooks, I was shocked at how supple they were. I thought they’d be stiff with rigor mortis, but they arched down like a hammock. I had to get on the bed of the truck and loop my arms under the hogs’ front legs and yank hard.

At the pit, Ricky asked me to stand back while he and Lynn rejiggered the carcasses into position at the lip of the open tailgate.

“Now, watch and learn,” said Lynn. Was that superiority etching his voice?

They abutted a large metal grid to the tailgate. With one elegant movement, considering they were yanking on something the size of your average businessman, they hauled the first hog onto the grid, cut-side up, and balanced it on the edge of the pit.

Ricky picked up a Black & Decker jigsaw, and without any warning to cover my eyes, began cutting off the bottom six inches of the hog’s legs. Every so often the saw locked, bucking against bone and tendon. The hocks, he said, had to be cooked at a different temperature and time because they were so much smaller.

“Here,” he said, tossing each one at me like they were a roll of paper towels. “Hold these, will ya?” Then he took a short knife and slit the hog down its spine to help it lie flatter.

“The trick is not to go too deep or else you’ll wind up cutting her in half, and all the fat and juices will leak out causing flare-ups.”

I nodded. And then in one deft movement, he flipped the bier carrying the hog up and over the side of the pit, so the carcass was gutted-side down. Applause erupted from the friends and waiting customers who had gathered around the pit.

“And that, my friend,” Ricky announced to me, “is how it’s done. And by the end of the week, you’ll be doing it, too.” He turned to the group of admirers and began glad-handing, as he walked back to prepare the remaining carcasses.

Alone at the pit, I looked at the hog lying with its backside up, and all its human qualities returned. There was the pinkness and the soft arch of a woman’s back. Spread eagle like this, the hog revealed deep dimples in its rump, the kind of dimples that make a bathing suit so alluring. I went to the bathroom and wept.

Later that day I was relieved of all duties, not because I cried, Ricky didn’t see that, but because I now looked cadaverous. I smelled awful, too, a cross between the suffocating odor of spoiled lard and the iron tang of a bloody handkerchief. How I ever saw the romance in the life of dirt-streaked vegetable purveyors and sweat-riddled butchers at Les Halles, the long-gone food market of early 20th-century Paris, is beyond me. At 278 pounds, with a soft heart and softer belly, the only role I was constitutionally fit to play back then would be a corpulent member of café society. As if I weren’t feeling enough the physical and emotional strain of my weight, Ricky blithely announced to everyone that afternoon that if he barbecued me, he’d get a mere 65 pounds of meat. He ushered in the realization that I was officially, undeniably, morbidly obese.

“Go back to the motel, clean up, and get some rest. I’ll see you back here at eleven tonight.” I was so tired, I just nodded and walked out to the car.

“There he is!” shouted Lynn, shoveling coals into one of the outdoor pits. “We weren’t sure if you’d make it, being these aren’t your normal-type New York hours.” He looked at Ricky and sniggered. Mike Williams, Brenda’s boyfriend, who had stopped by to say hi, didn’t want to encourage him.

“We work late in New York, too,” I said. “What do you want me to do, Ricky?”

I was to tend the fire with thirteen-year-old Zach, Ricky’s other son. In order to create the coals needed for the fire, Ricky, or Mr. Scott before him, had built a three-sided shed out of metal. Long, thin cuts of hickory wood were piled high in one corner and set ablaze. In the other, the burned-down coals of a previous batch were ready to feed the ever-hungry pits.

As Zach and I worked, he peppered me with all kinds of questions. Do you like New York? How long have you been there? Do you write about other things besides food? Are you rich? What’s Yankee stadium like? Have you ever been to the Statue of Liberty? Is Broadway really a wide street? Is it true that people are murdered there every day?

As I tried to explain that, no, New York City is actually a very safe place, he kept hammering away, making my hometown sound like the slasher capital of the nation.

“Don’t mind him,” Ricky said, laughing. “He can argue with a tree stump.”

As his inquest built, so did the fire. It became so hot the flames began licking at the slanted ceiling of the shed, and I had to back away and toss the wood onto the pile from a distance in order to protect my face. Zach just kept working and talking.

“For Chrissake, Zach, aren’t you dying?”

“Ah, you get used to it.”

Once we finished building the fire, we had to spread a pile of embers into the pits, careful not to raise clouds of ash, which would ruin the taste of the barbecue. Because of my performance and obvious discomfort, I was given the sensitively named “wussy shovel”—the one with the shoulder-high handle, which kept me farthest from the heat—while Zach got the regular, waist-high shovel.

I reached into my pocket to get a rag to wipe my face. Inside was something wet and sticky. I pulled it out: Because of the heat from the fire, my vitamin-E capsules, which I had forgotten to take, melted. Seeing me dig at my crotch, Lynn planted his shovel into the ground and shouted, “Hey, David, you ever been gaulded?” I cupped myself; it sounded too much like gelded for my comfort.

“Don’t you worry,” he said laughing. “I’m not coming anywhere near there with this.” He lifted the tip of his shovel. “Gaulded is when you’ve been sweatin’ so much that your balls and thighs get so chapped and irritated, you just go crazy. And let me tell you, baby powder and Desitin don’t do a thing. The only thing that works is cornstarch. What you do is put a sheet on the bathroom floor so’s the wife get don’t mad at ya. When you get out of the shower, you grab a handful of the stuff and you rub it all up in there.” I looked around me and all the men were nodding in dead earnestness, wincing as if they were witnessing an evisceration.

Then Ricky broke in: “David, I need you to put these hogs onto the pit.”

“Me?”

“Yup.”

Remembering what they did earlier in the day, I edged the metal grid up to the truck’s tailgate with Ricky and yanked on the hog’s legs, but I wasn’t as graceful as him. The hog was heavy, and I staggered as we carefully positioned the grid on the lip of the pit.

“Here,” said Ricky, handing me the jigsaw.

“Oh, no, really,” I said. “I got the gist of it. I don’t have to do it.”

“Now, David, if you’re going to learn how to do barbecue right—from one of the three best places in the country—” a smile curled in one corner of his mouth, like the upstroke in a third-grader’s handwriting, “then take this and cut off those legs.”

“I’ll do it! I’ll do it!” said Zach. I may have been repulsed, but I wasn’t going to be upstaged by a thirteen-year-old.

I grabbed the saw and hunched over one of the hog’s limbs. Ricky hovered over me, gently grasping my hand and showing me exactly where to make the cut. He spoke to me in the comforting tones of an air traffic controller talking a passenger through landing a 747. Suddenly, I felt oddly calm, even though I was about to cut off all four trotters of an innocent hog that not twenty-four hours earlier was busy eating, snuffling, and running about on its petite high-heeled hooves.

The vibration jolted up my arm, landing squarely in my elbow. The saw locked. “Just pull it out and start again,” coached Ricky. I did as I was told, and the saw whined and protested until more than half the hoof was cut, then, free from pressure, whizzed through the rest of the bones, muscles, and tendons until the hock came loose in my hand. I did the same to the remaining three hooves.

Ricky then silently handed me the short knife and nudged his chin toward the hog’s spine. I knew all eyes were on me. Either I finish preparing the carcass, or I’d be branded a sissy—that kid who couldn’t climb ropes in gym. Luckily, there was no locker to be stuffed into.

“Make just one long cut,” he said, “but don’t go too deep, now.”

I turned the knife over in my hand, finding the right grip, then I placed its tip at the top of the hog’s spine. I took a breath and slashed all the way to the butt end, but the knife was surprisingly dull. Ricky winced. “Place the knife in the same slit and press hard this time,” came the air traffic controller’s voice. As I did, I watched several inches of flesh fall open. But instead of feeling nauseated, I became fascinated by the process. No longer was it an animal with feelings, but rather an object, something to be examined, like a cadaver in gross anatomy class.

I knew what was left to my initiation, and, oddly, it was what I feared most: flipping the hog onto the pit. That they’re positioned so they cook skin-side up not only requires a good eye but also strength. And even though I’m big enough to block traffic in a supermarket aisle or force an entire row of people at the theater to spread out so I can claim my seat, I have no upper-arm strength—something Lynn noticed the moment he meet me.

“Alright, Mr. David,” said Ricky, “this is it.”

“Well, if I miss,” I warned, “I don’t have the money to write a check for a ruined pig.”

“That’s just fine. We take credit cards.” The men chuckled.

I grasped both ends of the metal grid and balanced it on my thigh. I remembered the up-and-over movement Ricky and the others had used in flipping the hogs onto the pit this morning. I slid my palms under the frame for greater support.

“Scream a lot,” said Zach. “It helps.” I heard no screaming before, so I knew I was being set up.

Humiliation crept down my spine like a trickle of sweat. The longer you stay like this, the longer they’ll laugh, I told myself. Without thinking, I heaved the grid and hog over the side of the pit, letting out a grunt, not unlike that of track athletes tossing the shot put. The force was so great the hog ended up hitting the far side of the pit.

The men erupted in applause. Ricky clapped me on the back. “Next time, a little less muscle there, Superman.” I grinned. So this is male bonding. If I knew it felt so good, I wouldn’t have hidden behind books, art classes, and my cousin Shirley’s turquoise Easy-Bake Oven when I was a kid.

As we cleaned up, putting the refrigerator cartons on top of the pits, Lynn burst out: “Ya know what? How about you coming over to the house and the wife can make us some dinner, then we’ll shoot off a few.”

“Shoot off a few what?”

“Rounds.”

“Guns?”

He nodded. I hadn’t shot a gun of any sort since I accidentally embedded a BB in Tommy Quental’s leg when I was ten. But the thought of holding that much power in my hands, of knowing I had the capability of downing a deer, a bear, or a local with mischief on his mind filled me with a sense of sudden and inexplicable awe.

“Sure,” I said.

On my way out that night, I grabbed two chocolate fried pies and dropped by the office to say goodnight to Ricky and Lynn; the rest of the guys had left long ago.

“You look like hell,” Lynn said to me.

“Oh, thank you.”

“You know, you’re in danger of becoming a redneck.”

“Why?”

“You’re standing in a barbecue joint at two in the morning with two fried pies in your hands. What else do you need?”

He was right. What else did I need at that moment? Nothing, except maybe a big ole red pickup truck.

That’s how the rest of the week went: an endless round of rotating hogs from the walk-in cooler, through the pits, until they reached Mr. Carver and the customers. Finally comfortable with me, Ricky relented and described the barbecuing process in exacting detail—something he swore he did only by feel; time and temperature, he said, had nothing to do with it. As we walked around the outdoor pits, he explained the hogs are fired anywhere from twenty to twenty-two hours. They slow cook at 195 degrees until exceedingly tender. Once done, they’re flipped so the meat is exposed, and mild sauce is splashed on, as is a generous sprinkling of salt. They’re then moved to the holding pit, which hovers around 160 degrees, and where they can rest for up to 48 hours, but most don’t stay there more than an afternoon. The warming pit upfront is kept at low 130 to 145 degrees, cool enough for Mr. Carver to handle.

I was determined to find meaning in Ricky’s barbecue. I knew from speaking to him there are about six cuts of meat customers can request: shoulder; “brown meat” or ham; the confusing-sounding catfish (aka tenderloin); middling, or bacon, which does tastes like a very tender chicken breast; ribs; and pig’s feet. Plus all of it can be chopped or pulled, bought by the pound, or put in a sandwich. And there are the toppings: three sauces, two coleslaws (mayo and vinegar), ketchup, mayonnaise, and onions. Mathematically speaking, that means there are exactly 4,608 possible combinations, and one of them I was convinced would work for me.

Throughout my stay, barbecue was my lunch, my dinner, my afternoon snack, my midnight supper. I approached the task methodically, eating snout to tail. On my cross-hog tour, certain things were crossed off the list almost immediately. Gone on Tuesday night were pig’s feet—interesting, although not my favorite. Middling was exceedingly moist and subtle, but I like more flavor to my pork. Same for catfish. The brown meat was flavorful, but a little dry. All were dropped on Wednesday. By Thursday, I had pretty much settled upon on the shoulder, which gave me three more days of rejiggering the extras until I found my perfect combination. The medium-hot and the hot-hot sauces didn’t see the end of the day; although I tried, the burn was too much. Vinegar slaw made it to Friday lunch but was edged out by the sweet mayo version. Round about Saturday, I hit upon the combination of a pulled shoulder sandwich with mayo slaw, ketchup, a few drops of mild sauce, and salt and pepper. It had enough sweetness to satisfy the indelible memories of barbecues past and enough true smoked flavor to call it authentic.

“You just can’t get enough of this now, can ya?” Ricky asked at the end of the week. The truth was I didn’t want to eat it again for an entire year, but at least I could with complete and utter honesty tell Ricky that like the hundreds of customers who line up outside of the store every week, I love his barbecue.

Sunday, the Fourth of July, was battle day. Ricky bounded in from the outside pits, clean-shaven.

“Mornin’, David!”

“Mornin’, Ricky.” He surveyed the scene outside of the store and smiled. Folks were already lined up, shading their eyes against the slanting light to peer in. It wasn’t even 8:30 a.m.

“Here’s what I want you to do,” he said. “You’re going to work in the dining room, giving out free T-shirts to everyone.” I deflated. After my nights of crotch-grabbing ribaldry, standing there like a sandwich board–wearing dolt handing out inaccurate claims felt like a demotion. I watched that crooked smile work across his mouth, and I understood.

“What?” he said with a self-conscious laugh.

“Nothing,” I said.

“Well, then, get to work.” And with that, he turned the key to the front door and welcomed the customers with a broad sweep of his lanky arm. For the first time, I saw he was a born flack, the Barnum of Barbecue. All this time, I thought I was playing him, coming down here to learn about barbecue in order to write about it. But he had masterfully spun the whole event to his advantage. I was his Yankee sideshow. All the newspapers had carried near-libelous accounts of this Washington Post journalist who had named Scott’s Bar-B-Q one of the top three in the nation. Ricky knew with their curiosity and appetites whetted, these customers would flock to the restaurant to try to wheedle out of me which of the three spots—win, place, or show—I had reserved for Ricky, all while they waited for their change. Lynn was right: Dumb like a fox.

Piled next to me were boxes of the offending T-shirts in all sizes. They were tan with maroon printing. An imposing Washington Post logo in a chunky gothic font stretched from nipple to nipple. Below, it read:

HEADLINE STORY

Scott’s Bar B Q

Lexington, Tennessee

Ranked within top 3 in the nation

July 2004

Owner Ricky Parker

Underneath was a logo of three piglets.

Within minutes customers who picked up their reserved barbecue stopped by to get their free shirts, and that’s when my glad-handing career began. I made small talk with politicians, Ricky’s childhood friends, God-fearing members of nearly every church in Henderson county, someone’s cousins once removed, as well as state troopers, who during the week were waved off when they dug for their wallets. I didn’t mind terribly. I found nearly everyone to be exceedingly gracious and welcoming, with the exception of a portly woman who poked her face into mine and asked, “So, did you think we’d be all barefoot and bucktooth?”

“As a matter of fact, ma’am, I didn’t know what to expect.”

“Well,” she brayed, “we may not be all Washington-sophistication down here, but we’re good people.” A dust storm of self-importance swirled around her.

I attempted to explain I don’t live in Washington, D.C., but she was too busy hugging her package of barbecue with one hand and collaring her young son with the other. “I’d like one shirt for me,” she said. “What size do you think I’d take?” I didn’t bite. When I didn’t answer, she huffed out a great compression of air and dug through the boxes herself. She enlisted a nearby woman to hold various sizes up to the expanse of her whale-like back. She eventually settled on an extra-large.

“And I’d like two mediums,” she said, nodding to her son. “He goes through clothes like wildfire.”

When I explained I was allowed to give out only one shirt per person, she rolled her eyes, gathered up her food, child, and clothes, and sauntered out.

Lynn kept the flow of customers streaming my way. “This here is David Leite,” he would begin, with the same unchecked pride as if he were introducing a homely daughter to a rich suitor. “He’s a writer for,” and here he would pause for effect, “…The Washington Post.” He took everyone’s obligatory look of interest as proof of a job well done and peeled off looking for more people to bring unto me.

When we were alone, I finally blew up: “Lynn, this is colossally irresponsible. You know I don’t nor have I ever worked at the Post.”

“Okay, calm down. No more, I promise.”

He got the hint and from that time on I was simply the “food writer from up north.” But no sooner had I got him under control were customers dragging spouses and friends over to meet the writer who they believe would put Ricky and B.E. Scott’s on the barbecue map. No matter what I did or said that morning, I was irrevocably woven into the fabric and mythology of Lexington lore. All I could do, I realized, was reconcile myself with it. Eventually, I was telling people that, yes, please stop by the paper when they come to D.C. to say hello; that, no, Woodward and Bernstein are nothing like the characters in the movie; and, of course, I’m invited to the White House all the time.

Not long after, Ricky came sweeping through the dining room. “Lock up the doors, Matt,” he told his son. I looked at my watch; it was 10:30. The silence almost hurt. Everyone dropped onto chairs around the long table in the middle of the dining room and stared off into the distance. Lynn doffed his hat and wiped his face with the sleeve of his T-shirt. Brenda lit a cigarette. The demands of customers, the astonishingly few mix-ups, the lengths Ricky went to make sure all orders were filled, even those of people who just happened to wander in after seeing the knots of cars in the parking lot was slowly fading from the room.

“And, that my friend,” Ricky said, slapping the table with his hand and repeating his word from earlier in the week, “is how it’s done.” The room broke out in laughter. I forgot my irritation at being a human advertising campaign because I saw that this isn’t about money for him. It’s about passion. He clearly loves his job and is committed to it in a way I’ve never seen anyone be devoted to his work. I was envious. And if the tension I occasionally felt between him and Tina during the week was any indication, yes, there probably is neglect going on in some areas of his life, as he said at dinner that first night at O’Charley’s.

Tina invited me to a family barbecue at her mother’s house later that day. I felt honored. I told her I’d be happy to go, but I needed to get back to the motel to clean up and pack first.

I’d like to say there was a grand conclusion to the week: an epiphanic, relaxing barbecue with a new extended family, but there wasn’t. While I dressed at the motel, weather reports crawled along the bottom of The French Connection warning of torrential downpours and golf-ball-size hail headed east from Memphis. My plane left Nashville first thing the next morning, and I didn’t want to miss it. Torn, I returned to the restaurant and told Ricky and Tina I was passing on the invitation.

“Well, it was sure nice having you here, David,” he said.”Don’t be a stranger.”

“I won’t. I promise.”

On my way out Lynn sidled up to me.”Are we okay about all the T-shirt stuff?”

“Absolutely. I forgot about it five minutes later.”

“Well, I just don’t want you to think I’m a rough and tumble southerner.” We laughed and shook hands.

I reluctantly said goodbye to everyone, all of whom were still sitting immobile at the table, and headed for Nashville. About thirty minutes later, I considered turning back to go to the barbecue, but in my rearview mirror, a wall of hail was pelting cars. I set the cruise control to 75 miles per hour to beat the storm, but I wasn’t worried. If I were pulled over by a state trooper, all I had to say was I’m a friend of Ricky Parker’s, and I’d be granted immunity—immunity of the Barbecue Fraternity. To cheer myself, I turned on the radio and listened to songs of deceit, loss, and longing, and I felt much, much better.