In the pre-balloon era, China was busily engaged in a charm offensive. Following October’s Communist Party congress, at which Xi Jinping won an unprecedented third term in office, Beijing made moves to stifle the combative and confrontational group of diplomats known as wolf warriors. Xi hosted German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in the capital, and condemned Russia’s threats to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine. The tone of China’s leading diplomats noticeably softened. Vice Premier Liu He, meeting with corporate executives in Davos, Switzerland, emphasized that China was back and open for business. And for the first time in almost six years, Xi planned to host a U.S. secretary of state in China.

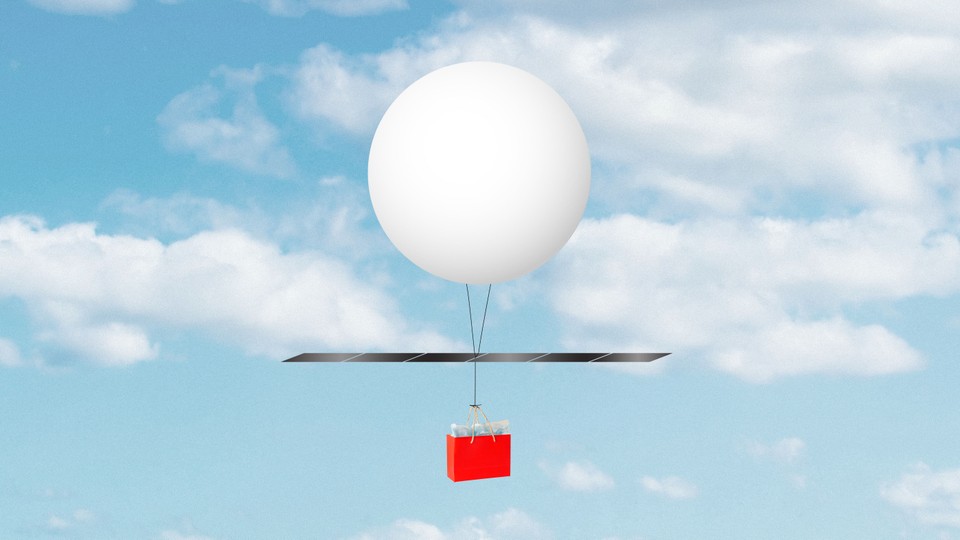

Then a Chinese spy balloon drifted across the U.S., and into America’s consciousness. The very brazenness of the act upended Beijing’s carefully tended diplomatic campaign and forced it into damage-control mode. At the same time, the balloon handed the United States, already engaged in heightened competition with China, a rare opportunity to rally both public concern and international solidarity.

Xi and his team must wish it weren’t so. Even before an F-22 fired a Sidewinder missile into the Chinese airship off the South Carolina coast, Beijing’s miscalculation was clear. Secretary of State Antony Blinken postponed his visit, the Biden administration denounced the violation of American sovereignty, and Republicans alternately blamed Beijing for launching the balloon and Biden for not downing it sooner. Now the United States has shot down three more airborne objects—possibly balloons, potentially Chinese, perhaps engaged in espionage—over Alaska, Canada, and Lake Huron, galvanizing further attention. Whether a product of hubris or incompetence, the Chinese-spy-balloon affair has derailed Beijing’s charm offensive and raised grave suspicions among Americans.

And not only, it turns out, among Americans. Soon after the first balloon appeared over Montana, a second one was detected floating across Latin America. Beijing claimed that it, like the first, was simply an errant meteorological airship blown off course—but apologized for violating Costa Rica’s airspace nevertheless. Taiwan then reported that it had been subject to dozens of spy-balloon overflights in recent years, and Japan launched an investigation to identify potential Chinese intrusions in its airspace. London began a security review and warned that balloons may have crossed British territory, while NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg observed that the spy balloon “confirms a pattern of Chinese behavior,” requiring allies to “step up what we do to protect ourselves.”

In recent years, U.S. policy makers and politicians have tried to raise public awareness of the challenge posed by China. Beijing wishes to revise the international order, they’ve argued, in accordance with its own vision of autocratic rule. China’s economic and technological power radiates illiberalism and creates national-security threats. Beijing steals intellectual property, conducts cyberattacks, and is building a world-class military. The United States and its partners must, policy makers have said, gird for long-term competition against a formidable adversary—a task made far more complex by our deep economic interdependence.

Their warnings have been only partially heeded. Americans have, according to polls, become somewhat more concerned about China in recent years, but it does not top their priority list. Allies and partners have grown more skeptical of Chinese intentions, and more interested in working with America to resist them, but they also wish to avoid any confrontation with Beijing. Here the balloon stunt—visible, politically salient, and transfixing—provides an opportunity.

There are rough antecedents, including the Soviet shootdown of Francis Gary Powers’s U-2 spy plane flight in 1960, and the collision of a U.S. Navy EP-3 surveillance plane with a Chinese fighter jet in 2001. Despite—or perhaps because of—the secrecy of those missions, the public fallout far outweighed the value of any intelligence that the operations obtained. The same is true today.

The Biden administration is already making the most of its opportunity. Officials now publicly refer to a fleet of Chinese balloons that have conducted surveillance over five continents. The State Department briefed representatives of 40 countries on the flights just days after the first balloon’s appearance. National-security officials are providing multiple public briefings as well, and they are moving to declassify information about Chinese activity. The continued appearance—and forcible downing—of airborne objects will keep attention focused squarely on Chinese activities.

This is the stuff that heightens public anxiety and brings about greater international solidarity. Protected by friendly neighbors and two oceans, Americans are unaccustomed to violations of their physical sovereignty by foreign nation-states. Exhortations to beware threats to the liberal international order, or warnings about Chinese activities in the South China Sea, can’t be half so effective at focusing public attention as huge airships spying on U.S. military installations. Learning that their own airspace may also have been violated by the Chinese government, for years, is likely to stiffen spines abroad as well.

[Garrett M. Graff: A history of confusing stuff in the sky]

Numerous countries have seen public opinion on China turn on a specific episode. For Australia, it was Beijing’s interference in domestic political affairs in 2019. In Canada, it was the seizure and detention, for more than 1,000 days, of two of its nationals. In India, border skirmishes turned the national mood, and in Britain it was the extinguishing of Hong Kong democracy. As strange as it sounds, for America and for others, Beijing’s spy balloons may supply a similar turning point.

For China hawks, however, this poses its own challenges. Yes, Beijing’s diplomatic harm offensive is convincing the skeptics to take Chinese ambitions seriously. The balloon will likely make the adoption of competitive strategies easier and quicker than if it had never taken flight. China’s miscalculation could lead to a broader awakening.

Yet policy makers must guard against overreaction as well. The United States has not calibrated its responses to past national-security shocks terribly effectively. America is slow to boil but quick to boil over. Those dismissive of the balloon stunt—it’s just a balloon; let’s not get worked up about a trifle—have it wrong, given the scale of Chinese ambitions and the means with which Beijing pursues them. But that does not imply that those aiming rifles in the air have it right. Competing effectively with China requires avoiding needless confrontation.

The news cycle will eventually turn away from Beijing’s balloon fiasco. Chinese leaders may recalibrate once again, and attempt to catch more flies with honey than helium. Yet this episode will likely shift perspectives for good, certainly in America and possibly abroad. For all the recent increase in tensions, the public has lacked a dramatic, concrete illustration of Chinese activities, one that would raise both public consciousness and the demand for action. Just as it was attempting to allay the fears and suspicions of the international community, Beijing supplied the fulcrum for a broader and more resolute coalition seeking to frustrate its designs.