Reading the early works of established, revered writers always reminds me of looking at a baby’s face: how it seems impossible to know the ways that visage will sharpen and emerge, how mushy it is, sometimes indistinguishable from others—but also, when looking back at photos once the baby is grown, how difficult it is to imagine that face turning into anything other than what it has become.

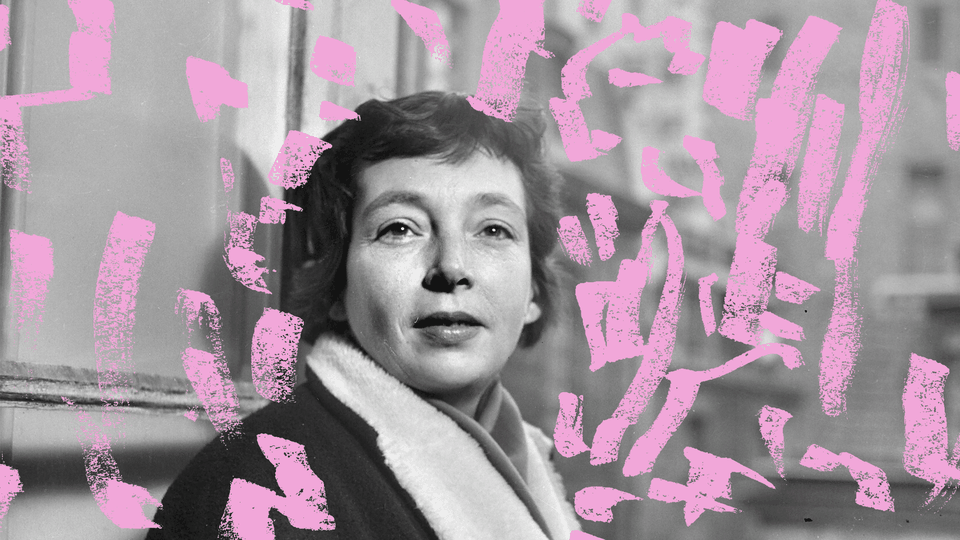

The French novelist Marguerite Duras’s second book, The Easy Life, which has just been translated into English for the first time by Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan, might not be much of a draw by itself. The thrill of reading it comes from seeing all of the ways Duras was already the writer she would spend the next 50 years becoming, from recognizing how the interests she cultivated throughout her career were already in progress.

If Duras’s power comes in part from the way her voice enmeshes you in its intensity, this early novel gives us a glimpse of how she learned to wield that voice. In The Easy Life, Duras tries, often unsuccessfully, to elucidate complicated and abstract themes: identity and gender, violence and desire. By The Lover, her most famous work, which she published 40 years later, she had sharpened the tools at her disposal, replacing overly hazy descriptions with short, concrete scenes. Most important, the novel allows the murkiness of everyday emotion to live on the page without straining to explain it, trusting the universality of human experience to render these ideas legible to the reader.

Set in mid-20th-century France, The Easy Life is a straightforward-enough story, told mostly in a familiar, linear form. The protagonist, Francine, is 25, still living at home and grappling with the breakdown of her family. We track her attempts to understand her place in these events and to make sense of her relationship to the wider world. The novel begins just after a vicious altercation between Francine’s uncle, Jérôme, and her brother, Nicolas, which Nicolas starts after learning that Jérôme has been sleeping with his wife, Clémence. Jérôme soon dies from his injuries. Francine is guilt-ridden: She’s the one who told Nicolas about his wife’s affair. Clémence soon leaves Nicolas and her newborn baby to stay with her sister; Francine, feeling responsible, helps care for the infant, allowing him at one point to suckle at her breast.

[Read: A novel with a secret at its center]

The book contains all the portents of the novelist readers would come to know. As in many of her other works, Duras creates an atmosphere in which violence is palpable and constant—not an impulse embedded in a single character so much as a chemical hovering in the air. Although it is usually the men who act out the brutality, it is often the women who function as the catalysts. It is often the women left to deal with the consequences.

After a second and more devastating death in the family, in which Francine also feels implicated, she leaves her mother’s home for the town of T, close to the sea, to mourn: “Who was I, whom had I taken for myself until now? … I couldn’t locate myself in the image I had just come upon. I floated around her, so close, but there existed between us something like the impossibility of uniting.” This is the section that most reads like the mature Duras: the fluidity of identity, the impossibility of ever fully understanding other people’s wants, needs, and intentions, let alone one’s own. It is also, thinking again of a baby’s face, the mushiest. The ideas—the mystery of the self, the unrelenting trudge of time—are grippy and knotty, and Duras, by trying too hard to pin them down, often loses hold of them.

Duras ties up the final section of the novel quickly and awkwardly, with Francine receiving a marriage proposal from her brother’s friend. Moving associatively rather than linearly, The Lover is celebrated for its courageous form. Meanwhile, there’s something disappointingly predictable, almost anachronistic—reminiscent of Jane Austen or the Brontës—about the way The Easy Life ends as if it were a straightforward marriage plot.

[Read: Making peace with Jane Austen’s marriage plots]

Duras wrote The Easy Life in 1943, on the cusp of turning 30. She wrote The Lover—which is based on an affair she had with an older Chinese man when she was living in Indochina as a teenager—in 1984, at 70. The first paragraph of The Lover introduces us to the image of our narrator’s aged face: “One day, I was already old, in the entrance of a public place a man came up to me. He introduced himself and said, ‘I’ve known you for years. Everyone says you were beautiful when you were young, but … I prefer your face as it is now. Ravaged.’” Having read both books in quick succession, I also felt this admiration, the power and crackle of that ravaging.

The Lover unfolds through repetitions. Despite its experimental format, Duras notably unspools her story through specific moments, actions, visuals: the narrator’s face at different ages, photos of her son, the clothes she wears. She lets us sit inside contradictions, tensions that won’t or can’t be defused. And by shifting decades between paragraphs, colliding seemingly disparate images, Duras illuminates not only the complexity of the affair but also the inextricable links among themes she explored over the course of her career. The Lover examines almost every idea, in other words, that The Easy Life does, but with a deftness that can be acquired only through experience and time.

What, then, can we glean from lesser, mushier objects made by people who later give us the same obsessions in a sharper, clearer form? Not least is the knowledge that nearly all of the writing we do is practice. If The Lover is singular, The Easy Life is proof that singularity is built, slowly and deliberately, through continually circling the same handful of preoccupations, through deconstructing and reconsidering form. To create art is nearly always to fail, but in that failure comes the acquisition of more and more tools that might help us fail better, more daringly, the next time.